-

- Centre de recherches en histoire et épistémologie comparée de la linguistique d'Europe centrale et orientale (CRECLECO) / Université de Lausanne // Научно-исследовательский центр по истории и сравнительной эпистемологии языкознания центральной и восточной Европы

-- W. K. MATTHEWS : « The Japhetic Theory», The Slavonic and East European Review, Vol. 27, No. 66 (Dec., 1948), pp. 172-192.

[172]

"It is more difficult to destroy than to create " is only part of the truth. We shall be nearer to its uncovered source if we say : " Not only is it difficult to destroy, but we have not the strength to do so.”

N. Y. Marr, Yafetidy (1922).I

The “ new linguistic doctrine ” (novoe uchenie o yazyke), which was formulated in the U.S.S.R. in the course of the nineteen-thirties and has become the corner-stone of Soviet linguistics, derives ultimately, in scope and style, from the Japhetic theory, advanced before the Revolution and revised in the twenties in terms of Marxism by N. Y. Marr (1864-1934). The phases in the development of this theory represent, in some cases, radical shifts in Marr’s own thinking, and this makes it desirable to know something about his origin and backgrounds.

Marr tells us a great deal about himself in an autobiographical note published in the periodical Ogonyok (No. 27/223) in 1927. He was of mixed parentage : his father was Scotch, his mother Georgian, and he himself was born and bred in Georgian surroundings at Kutaisi (Kutais), in Transcaucasia. It was there too that he attended the grammar school (Classical gymnasium), at which he was able to improve the “ broken ” speech he had acquired at home, where a mixture of faulty Russian and Georgian served his parents as the medium of communication. He successfully completed his school training with the determination to read Oriental languages in spite of attempts by both schoolmasters and schoolmates to dissuade him. Accordingly he entered St. Petersburg (Leningrad) University in 1884 and set about perfecting himself in four distinct groups of languages: Indo-European (Persian), Iverian (Georgian), Semitic (Hebrew, Syriac, Arabic), and Altaic (Turkish). At the same time, he participated in the purely verbal separatist movement which was then exercising the minds and emotions of Georgian students. Two years afterwards, primed with a knowledge of Semitic, he was struck by the similarities between his mother tongue and Arabic, and in 1888 published an essay, “ The Nature and Characteristics of Georgian,” in the Tbilisi (Tiflis) Georgian newspaper Iveria (No. 86), in which he gave a foretaste of his theory by correlating Georgian, lexically and structurally, with Semitic. A fuller formulation was to come much later, when he had already

[ 173 ]

over a hundred publications to his credit, in the ten-page preface to Basic Paradigms of Old Georgian Grammar (St. Petersburg, 1908)[1] entitled “Preliminary Remarks on the Relationship of Georgian to the Semitic Languages”[2]. Long before that time and at the end of his university studies, Marr, on the advice of Professor K. P. Patkanov, had begun to devote himself increasingly to the problems of Armenian philology. Apparently his temporary neglect of Georgian was largely due to the keen opposition of his compatriots at home, headed by the nationalist Prince Cavcavadze, who had taken exception to Marr’s discovery that the Georgian Bible had been translated from the Armenian and that the fable of Sota Rust'aveli’s 12th-century romantic poem " The Man in the Panther’s Skin ”[3] was of Persian origin. Marr himself admits that he had become a Caucasian “internationalist” and was now strongly opposed to nationalist tendencies.[4] By 1901, though he had still to take his doctorate (and did two years later), he was elected to the university chair of Armenian in spite of considerable opposition from both above and below, and in 1912 he became an active member of the Imperial Academy of Sciences. Meanwhile, with his passion for synthesis, Marr had been sporadically pursuing his idea of Japhetic unity into the extra-linguistic fields of archaeology, history, and literature, and at the same time he had brought his researches out into the open air by repeated visits to Armenia, where in 1892-1893, for instance, he participated in excavations at the mediaeval burg Ani, which brought him the conviction that there were no inviolably isolated national cultures. “All my creative linguistic ideas,” wrote Marr later,[5] “ are not the outcome of work in the study. They were conceived and moulded in the course of my contacts with man and nature, in streets and market-places, in deserts and on the seas, in the mountains and in the steppes, by rivers and springs, on horse-back and in trains—anywhere but in the study”. The significance of this rather exuberant statement outweighs the modest disavowal of his “profound knowledge of all the Caucasian languages,” admittedly a “ quite unnecessary legend,” thrust on him by uncritical, if genuine admiration.[6]

[ 174 ]

Among those "creative ideas” were ideas concerning the origin of human speech, which persistently thread the pattern of his linguistic work and ultimately lead him to abandon philology and archaeology for purely linguistic study, for this transition can look back equally on the study of inscriptions and on archaeological investigation.[7] Parallel to his field-work on dead languages[8] and ancient inscriptions, Marr makes a study of living speech radiating northwards from his Caucasian (Georgian-Armenian) base. Here Georgian, as living Japhetic, was the starting point of his studies. Against the background of his mother tongue he first proceeded to investigate its congeners, some of which (e.g. Svanetian and Laz) he found more “primitive” in certain respects, than 9th-century Old Georgian, and then the Caucasian languages proper. After that his researches extended south and east under the reasserted bias of the past, to include all the literary languages of the Old World. In 1927, in the middle of his miniature autobiography, he admits having studied all except those of the Far East, which he appears to have started learning only then. At that moment, surveying his linguistic horizon, like Cortez the discovered Pacific, he could exclaim: “ Not only has the isolation of Georgia disappeared, but that of China too. We are on the point of establishing the fact that from Japan and China to the Atlantic the basic terminology of prehistoric culture is identical. All words in all languages may be resolved into four elements." Marr acknowledges the incompleteness of his theory, which by this time had been clearly formulated and was already current in the more progressive Soviet linguistic circles : the languages of Africa and America, he declares, ignoring Austronesia by a curious oversight, remain to be brought in, and the chronology of the various typologically significant language-systems determined.

But all this anticipates by a considerable leap of years the development of the Japhetic theory from its earliest hintings in 1908 to its reiterated authoritative exposition in the nineteen-twenties. The next stage, after the comparison of Georgian with Semitic (i.e. Hebrew, Syriac, and Arabic) and the recognition of a genetic bond between Japhetic and Semitic, was the study of living dialects" of the Iverian type, from among which he chose Chan (Laz) because of its lexical contribution to written Armenian

[ 175 ]

(Hai) and “points of contact” between it and the language of the Susa inscriptions. In preparation for his grammatical study of Chan he visited Turkish Lazistan, where the bulk of Chan-speakers are settled. The preface to his Grammar[9] avers that his treatment of Chan is necessarily superficial in view of the shortness of his stay, but he offers it nevertheless as an encouragement to further analysis of the Japhetic-Semitic equation. After an excursus into the interpretation of the Achaemenid cuneiform inscriptions “of the second category" in terms of Japhetic linguistics,[10] Marr returned to his Caucasian researches, which by now had taken an extra-Iverian, northward trend, and produced a significant paper on Abkhaz in 1916[11. Here he discusses the attractions of the phonetic complexity of this language and makes it the focus of his reconsideration of Japhetic, whose features he had already traced in his study of Chan and the “cuneiform’’ language of the Achaemenid inscriptions. The stimulus of the Revolution, which Marr appears to have accepted from the outset, may be seen in the circumstances under which his first complete elaboration of the Japhetic theory was made in 1919. “ The Japhetic Caucasus and the Third Ethnic Element in the Creation of Mediterranean Culture "[12] was read as a paper at a meeting of the newly-founded Russian Academy of the History of Material Culture and published as a pamphlet in Leipzig in the following year. This capital work became known to European scholarship in F. Braun's German version, which was published in 1923,[13] i.e. early enough to influence, so far as the Caucasian languages were concerned, the rather fanciful and superficial linguistic synthesis of Father W. Schmidt.[14] At that time such influence was quite possible, because Marr, as a self-confessed “ formalist," [15] still accepted the prevailing Indo-European doctrine of the linguistic archetype (protoglossa, Ursprache) and such variations and corollaries as the substratum theory, the correlation of language and ethnos, and, on another plane, the theory of culture diffusion. In 1923 Marr’s close association with the revolutionary victory of five years before resulted in his election to the presidency

[ 176 ]

of the Central Soviet (Council) of the Intellectual Workers' Department. By 1924-1925 his innate as well as outwardly stimulated opposition to Indo-European linguistics had become fully articulate. From then onwards the protoglossa and monogenesis are relegated to the ashes of exploded fictions, and social and economic factors emerge to explain the gradual agglomeration of originally diverse tribal (ethnic) languages into systems of expression, which, viewed diachronically, exhibit stages (stadii) reflecting the evolution of social thought-processes.[16] Here we see the conscious fusion of the Japhetic theory with the Hegelian-Marxist dialectic. The new standpoint was adopted by the Leningrad Japhetic Institute, which Marr had founded with the consent of the Academy of Sciences in 1921,[17] and by the Moscow Institute of Nationalities. Linguistic “nuclei” (yacheiki) were established in the provinces (e.g. the Caucasus, Central Asia, Kazan) by the younger linguists who had enthusiastically taken up Marr’s views. The provinces indeed were more eager than the centre, where the Japhetic Institute was belatedly (1931) renamed the Institute of Language and Thought (Institut Yazyka i Myshleniya). This change of name was connected with Marr’s acceptance of the Marxist conception of the unity of thought and language, and with his joining the Communist Party (1930) and becoming a member of the Central Executive Committee (VTsIK). The meaning of the change is plainly indicated by Marr himself in a semi-autobiographical address delivered at the 110th anniversary session of Leningrad University in 1930.[18] "The Japhetic theory,” he assures us at the end of his address, "embodies the national-proletarian antithesis to the feudal- bourgeois great-power thesis,” and elsewhere in the same paper he adds : “At the present time the Marxism of Japhetic linguistics is beyond dispute, the more so as the Japhetic theory presents, historically or in specially studied material, though not in essence, a kind of parallel to Marxism or a variant of it.” Marr was rewarded for his services to the Party with the Order of Lenin in 1934, and it was in that year that this extraordinary man died.II

The Japhetic theory, as we have seen, is older than the Revolution, but was elaborated after that event, and the changes and accretions which its more advanced stages reveal were due to the

[ 177 ]

expansion of linguistic knowledge by the annexation of fresh languages. It began as an intuition in one who was familiar from childhood with several diverse languages acquired in the ordinary course of living and by study, and at first it was intended to cover and explain only the linguistic complex of the Caucasus. The scope of the theory expanded till it ultimately came, in Marr’s own words, to include all the languages of the world, living and dead, on equal terms. It is pre-eminently a reflection of the vicissitudes of Marr’s psychological development, and its breadth and variety are a verbal parallel to the ethnic and linguistic structure of the U.S.S.R. The Japhetic theory is in the first place the mind of Marr himself, and secondly where the personal merges in the collective, a vivid picture of the linguistic energy of the U.S.S.R. in its ideological self-sufficiency and militant opposition to the Indo-European (Aryan) linguistic dogma of peninsular Europe.

The earliest pre-revolutionary statement of Marr’s hypothesis is little more than a suggestion. It has its origin in the equation of Georgian, as a form of Japhetic, with Semitic, derived from a collation of passages in works by F. Muller[19] and the Georgian scholar A. Tsagareli,[20] which establishes an obviously plagiaristic relation between the two.[21] Both these authors detach " Caucasian ” from Indo-European and “ Uralo-Altaic,” and draw a parallel between Caucasian and Basque. This would seem to be the source of what was later to become the Japhetic theory. It began then as an attempt to characterise, place, and explain the linguistic system of the Caucasus, and the first step was to link Georgian with literary Semitic. “The Georgian language,” wrote Marr in his mother tongue in 1888, “ both flesh and spirit, i.e. lexical roots and grammatical conformation, is related to the Semitic languages, but the relationship is not so close as that among the Semitic languages themselves.” These words are taken from the concluding paragraph of Marr’s first published work,[22] and the idea they contain was developed in Basic Paradigms of Old Georgian Grammar twenty years

[ 178 ]

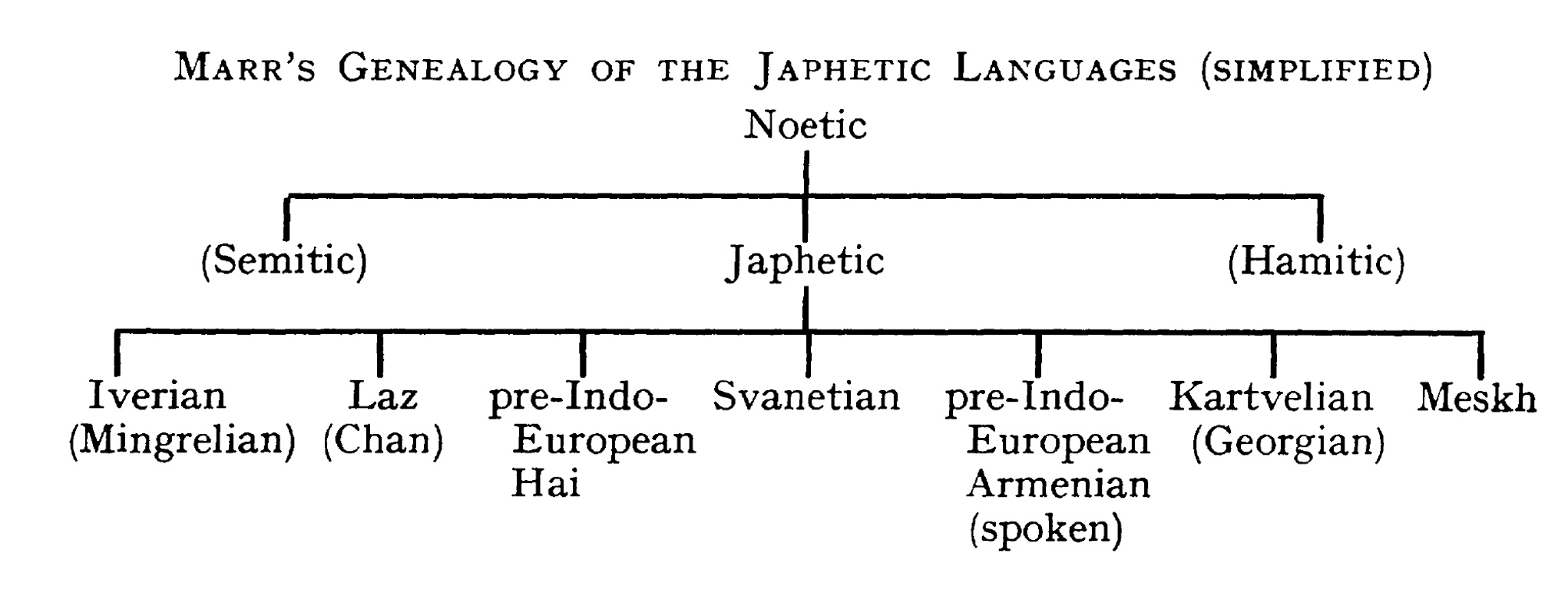

later. In the preface to this book Marr concedes that Georgian contains very much that is alien to Semitic. "That is why it cannot be regarded as Semitic" though it is "to some extent” connected with the Semitic languages, the “extent” being defined as cousinship or extraction from the “brother languages" — Protosemitic and Protojaphetic. This assertion rests on a comparison of Georgian words of various grammatical categories, mostly verbs, with Semitic equivalents (e.g. Sem. šms, Geo. mze, sun ; Sem. hbl. Geo. suli, soul, breath ; Sem. hrb, Geo. srba, ran). In Marr’s next study, the preface to his Chan grammar (v. supra), a genealogical table of the Japhetic languages is given. The correlation of Japhetic with Semitic (and tentatively with Hamitic) is retained, and all three families (stocks) are derived from an hypothetical Noetic (< Noah). An examination of the individual languages at the foot of the table shows that Marr has confined his researches mainly to Iverian types (Mingrelian, Laz, Svanetian, Georgian, Meskh), to which he adds pre-Indo-European (pre-Aryan) Armenian in its two allotropic varieties, written (Hai) and spoken.

So far then Marr has not sallied out of his Transcaucasian base, and the twin foci of his linguistic researches — Armenian and Georgian — stand revealed. By 1912 he had already discovered the dichotomy of sibilant and spirant (glottal),[23] with the subdivision of the former into hush and hiss types (sifflantes and chuintantes). The major antithesis may be illustrated with examples from Iverian (“ Kartalinian ”) : Geo. suli, Ming, suri, Svan. qun (< hun), but it plays a larger part in the phonetic analysis of the wider “Japhetic" at a later stage. In all these early works, too, Marr uses what was afterwards to be elaborated as the Japhetic alphabet,[24] to transcribe both written and unwritten languages. It is a relatively transparent

[ 179 ]

Greek-Latin-Cyrillic conglomerate and was formed primarily to meet the requirements of purely Japhetic linguistics, and even in 1926 Marr admits that it requires reconstruction and enlargement, because its range is ultimately to coincide with the limits of linguistics “on a planetary scale."

The next stage in the expansion of the Japhetic (till then purely Iverian) theory is reflected in the temporary abandonment of rock and print for life, the inscribed and written word for the spoken. The centre of curiosity is now held by Abkhaz,[25] a northerly non-Iverian type, with which Marr had become acquainted in the field. This language has a totally different grammatical structure from that of his mother tongue. Syntax here, as Marr points out, “plays the role of morphology," i.e. word-order expresses what formal features do in other languages; the connectives are elusive, often embedded in words; and the verb functions as a nucleus to a complex of centrifugal associates. “The Abkhaz-speaker," writes Marr, “has a clear conception of the total complex of particles and stems" and “can even translate it faultlessly into another language, but when you ask him about the constituent parts of the complex, he feels quite at a loss, and when he has to explain, he makes contradictory statements." Abkhaz was the starting point of his penetration into the terrain of Caucasian proper (North Caucasian), which he ultimately annexed to his theory. And now he is inclined to regard his earlier approach to the problem through Georgian and Armenian as mistaken, especially in its linguistic aspect, because a true pan-Caucasian perspective can obviously be obtained only by “a profound study of all the montane (gorskie) languages," including Abkhaz, which, incidentally, gave him some assistance in the decipherment of Old Elamite (Chaldean).

We now come to the first post-revolutionary statement of the Japhetic theory (1919), which, in translation, made Marr’s views known to Indo-European scholarship and provoked the challenge and hostility of many European reviewers. At the same time Marr’s Indo-European-trained linguistic imagination was, as a matter of course, still apt to conceive the Caucasian languages as a separate bloc, nearer to Semitic than to Indo-European, but his growing opposition to the comparative-historical method favoured by Indo-European linguistics already expresses itself in determined tones. “Indo-European linguistics, exploiting the procédés of natural science," says Marr, “adopted the philosophy of a society

[ 180 ]

based on religion and substituted linguistic for the religious divisions of mankind, isolated the circle of Indo-European languages, and devoted itself to the exclusive and separate study of the Indo-European peoples. ... It transferred to the Indo-European (Aryan) race the view of confessional theology regarding the chosen people, whose varieties inhabit mainly the European world."[26] Indo-European linguistics reached its creative zenith in the eighteen-seventies and eighties and then began to dogmatise from its achievements. This dogma — largely German — was affected by the political moods of Germany after 1870, as indeed the Japhetic theory has been by the moods prevalent in Russia since 1918. “As an ethnological science interested in linguistic origins," Indo-European linguistics “expired" in 1880 and became merely a workshop for the elaboration of the comparative-historical method. Marr, however, acknowledges that the invention of technical procédés for the intensive study of languages belongs almost entirely to Indo-European linguistics, although at the same time he asserts, rather unjustly, that its contribution to the “extensive" study of languages has been "exceedingly limited."[27]

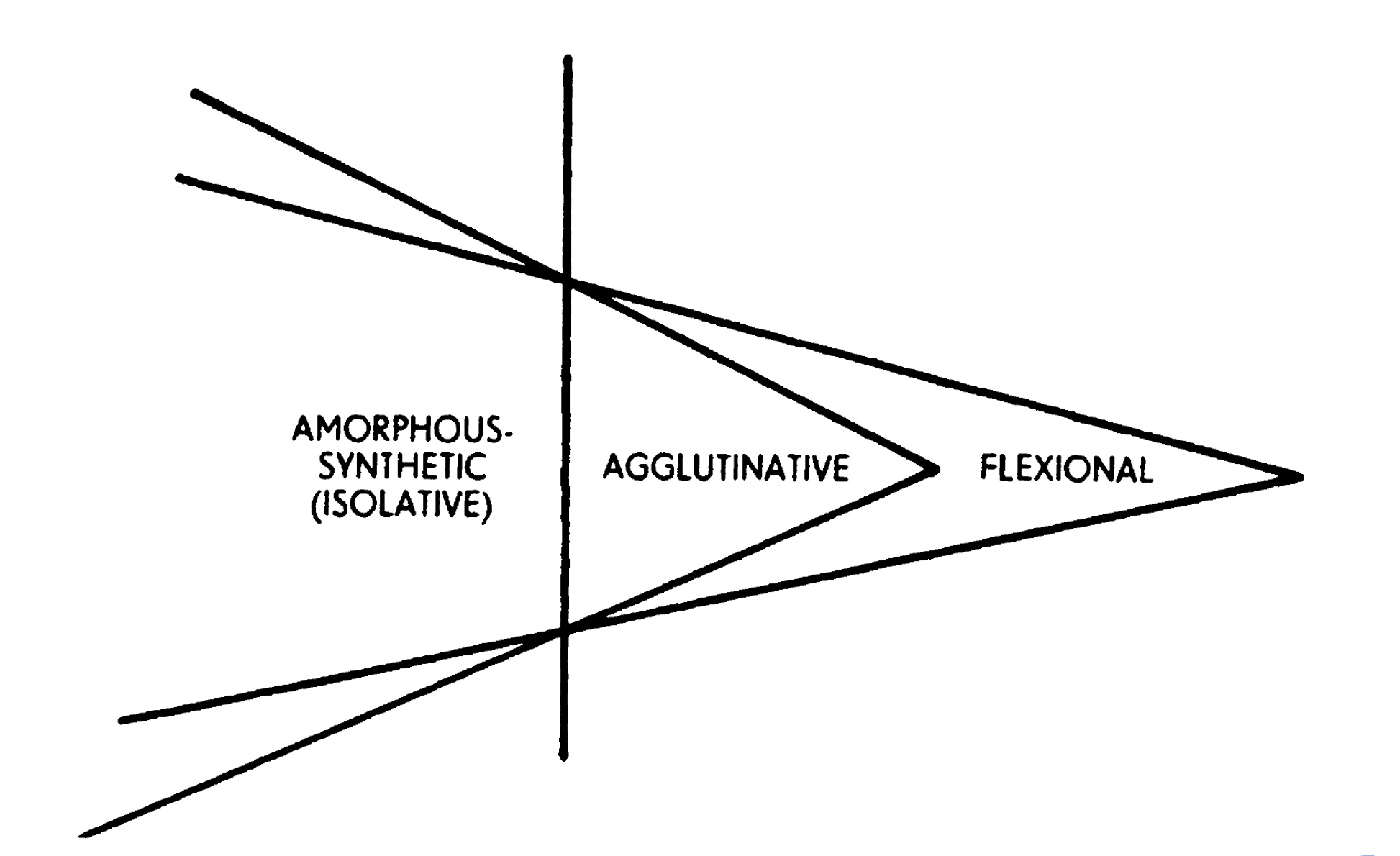

In the title of his essay, from which we have just quoted, Marr mentions the “ third ethnic element in the creation of Mediterranean culture." This, next to — and historically prior to — the Semitic and the Indo-European, was the Japhetic. Though Marr distinguishes the language “families" of these peoples as such, his interpretation of Japhetic is novel and already contains the outlines of his later definition. The Japhetic languages, apparently, are not based on a uniform archetype (protoglossa), but on the transformation of linguistic types as the result of miscegenation. They illustrate all three stages of language-building (glossogeny): the amorphous-synthetic (i.e. isolative), the agglutinative, and the flexional, in that chronological order. The morphemes of the last stage, we are told, are the outworn auxiliaries of the agglutinative period, and these in their turn, the word-units of the amorphous-synthetic. Linguistic morphology at each stage reflects the prevailing social order. The auxiliaries of the amorphous-synthetic period are anatomic terms (membra corporis) : in this period language is regarded in terms of the body and its parts in their physical relationship. Later these words, e.g. face, brow, eye, ear, nose, hand, hip, become prepositions and postpositions meaning “forward, in the presence of, over, etc." Japhetic linguistics claims also to have elucidated the pronouns, which are intimately connected with flexion. Primitive

[ 181 ]

declension would seem to have been a juxtaposition of name and pronoun, which later became fused, i.e. the former was provided with morphemes to express grammatical relations. The amorphous-synthetic period was the period of the herd, the agglutinative—of the clan (rod), the flexional — of the individual (litso). The differentiation of individuals resulted from a long process of evolution, which implied a steadily growing awareness of the antithesis of the individual person to his human environment. The numerals too, Marr pursues, are connected with parts of the human body (1 = mouth, 2 = lips, hands, 4 = feet, e.g. “ quadruped”, 5 — fist, hand, pyaternya). Primitive numeration extended only to 5-6, after which the idea of “many” expressed by the two hands, i.e. a multiplicity of digits, obtruded itself. “Two hands" at a later, numerationally more articulate period meant “ten.” The intervening units were expressed with the aid of the first five or six by addition, multiplication, and subtraction. Parts of speech did not originally exist; verb and noun were not contrasted; even notions like “to have” and “to dress” meant, as Georgian suggests, “he has fat” and " he puts on fat” respectively. Thus polysemy appears to have characterised the early stages of speech, and this had its inevitable parallel in undifferentiated sound-complexes, of which modern Abkhaz and Lezginian give some notion, although it is only an atavistic reflection of phonetic prototypes which occupied the margin between socially valid sounds and inarticulate herdcries.[28] The Japhetic Caucasus, as the foregoing illustrations imply, represents in microcosm the concentration and hybridisation of a large number of language types. Still adhering to the Indo-European conception of the linguistic family, Marr fixes the separation of Japhetic and Semitic at the onset of the flexional stage (stadiya), and the occupation of the Caucasus by the Japhetites is presumed to have followed this tertiary emergence from the two consecutive earlier types of typological transformation, viz. the amorphous-synthetic and the agglutinative. The Indo-European languages penetrated the Caucasus and produced hybrid types, illustrated by composite ethnic names (e.g. the double totem horse-metal, Iber- Yon). Exploring the geographical extension of the Japhetites, Marr discovers the presence of the Japhetic element in the Balkan (e.g. Pelasgian), Appenine (e.g. Etruscan), and Iberian or Pyrenean peninsulas (e.g. Iberian, Basque). Marr thinks Basque was hybridised in the Caucasus and describes it as a transitional, agglutinative-flexional type. The ethnogenic migration of the

[ 182 ]

Japhetites in prehistoric (Mediterranean) times took place from a Caucasian focus and point of departure, perhaps the Armenian massif, by two routes : (i) a maritime and southern, across Anatolia to the Mediterranean islands and peninsulas, and (2) a continental and northern, along the northern shore of the Euxine and “downwards” into the three southern peninsulas. Marr also envisages the possibility of an Iberian (i.e. Iverian) migration to the Pyrenean peninsula by a southerly (African) route via the Levant, possibly from a Mediterranean terminus a quo. The isolated Vershiks or Burushasks of the Pamir node (the Indian "Caucasus ") show, according to Marr, an Armenian affiliation in speech and may therefore represent a migration from a more westerly point of dispersion. Marr thinks the Japhetites occupied the Mediterranean basin prior to the "dawn” of linguistic flexion and regards them as the originators of material culture (fire, metals), which he conceives as radiating from the "Promethean” Caucasus. The Tower of Babel myth, on these terms, is no more than the story of “Japhetic reality.” Originally then there was one speech in the pre-Indo- European Mediterranean world — Japhetic, and the coup de grâce to Japhetic unity was administered by the emergence of Indo-European, which induced the process of miscegenation — in itself essentially a process of re-creation. In this way, Marr concludes, Japhetic has contrived, if only vicariously, to participate in the creative remodelling of European world-culture. Subsequently Marr was to modify these views, which in course of time began to strike him as too "caucasocentric,” and the term Japhetic itself was destined to be reinterpreted not as a “family,” but as a "system.” He also abandoned the ideas of migration and the substratum for the idea of transformation in situ.

We have here reached the fourth pre-Marxist phase[29] in the evolution of the Japhetic theory, which may be illustrated diagrammatically by five concentric circles. The innermost (focal) circle represents the first (dropped stone) stage, and the outermost — the final, inclusive stage of primordial human speech. The first two cover an historical phase, the third is protohistoric, the fourth — prehistoric, and the fifth — palaeontological. Phases one and two are represented by the equation of Georgian and Semitic (1888) and the discovery of Caucasian Japhetic (1912) respectively; phase three is that of cuneiform Japhetic (1916) ; phase four — of Mediterranean and Pamiri Japhetic (1919) ; and phase five — of primitive speech

[ 183]

(1925). From the standpoint of method, the first three phases disclose the use of the comparative-historical, and the remaining two — of the palaeontological.

Starting from hints dropped by A. Kannengiesser (1853) and F. Müller (1864), Marr at length arrived, by a succession of cyclical enlargements of his theory, at a coherent word-picture of the origin and development of human speech as a function and facet of human social development. At this juncture we observe the intrusion of the Hegelian-Marxist dialectic, which Marr adopted, after devoted study, about 1924. From then onwards the Japhetic theory assumes its final expression. As a system of materialist linguistics it now has a twofold aspect: it still continues to analyse and to elaborate the complex of Japhetic languages, and at the same time it seeks to establish general norms of linguistic development from the prephonic (linear) to the flexional stage by applying the concept of transformation from one stage (stadiya) to another, which Marr connects with the long-term periodicity of sociological change. Thus, the emergence of Indo-European from Japhetic was conditioned by the discovery of metals and agriculture, for Marr has here revised his former view connecting the metals with Japhetic. To the investigation both of the Japhetic languages and of the “stadial" development of human speech Marr applies the palaeontological method as against the comparative-historical method of Indo- European linguistics, which he openly discards. The difference of method is ultimately due to a difference of outlook, and this is reflected in the relatively greater breadth and “objectivity” of the palaeontological, which draws on other disciplines, such as sociology, archaeology, comparative religion, folklore, anthropology, and ethnography — all of them neglected by the other, purely linguistic method. Marr seriously connects linguistic with socio-economic phases of development[30] and, following the findings of Marxist sociology, emphasises the revolutionary “shifts" (skachki) or spasmodic momentum of language, which transmutes earlier linguistic material into later, to meet the requirements of changes in the social and economic order. The method of palaeontological analysis makes possible the comparison of languages at different levels of development by juxtaposing coeval strata: it studies language in “polystadial" (polychronic) section or in process of growth, and so substitutes a dynamic or kinetic for the static Indo-European view. The old typological divisions — amorphous-

[184]

s ynthetic, agglutinative and flexional[31] — are seen to be real enough in terms of the Japhetic theory, which regards them as three chronologically distinct transformations of speech, while insisting that “primitive” languages are related typologically, not phonetically. Some Japhetic types embody the triple metamorphosis, but seem nevertheless to prefer one stage to the rest, e.g. Abkhaz is mainly amorphous-synthetic, though it has traces of the other two types ; Georgian is in process of development from the agglutinative to the flexional stage, but is not without signs of amorphism ; and Indo-European and Semitic are only apparently more uniform in type.[32] The following diagram will illustrate the symbiosis of the three stages in a particular language or language-group.

Ill

The Japhetic languages, so named to complete the Shem-Ham- Japhet trinity in linguistic nomenclature, without at the same time implying their common origin, now include both living and dead languages. The first group contains most of the geographically Caucasian languages, i.e. Caucasian proper, Iverian, and Armenian, together with Basque and Burushaski (Vershik) on the western and

[ 185 ]

the eastern mountain marches respectively of the old Japhetic area. To the group of dead languages belong the fragmentary Hittite, Cretan, Elamite, Sumerian, Chaldean, a number of obsolete Anatolian languages, Etruscan, Neo-Elamite, Median, and the ancient written forms of Georgian and Armenian. Scythian, according to Marr, still remains an apple of discord between Indo-European and Japhetic claims. Cimmerian, Iverian, and Iberian, on the one hand, and Gurian (a form of Iverian) and Ligurian, on the other, are equated etymologically.

The distribution of present-day Japhetic languages shows them to be the relics of languages formerly spoken all over the Mediterranean area in “Afroeurasia,” as well as in America, Austronesia, and Australia. Marr is careful to point out that Japhetic does not constitute a “family" like “Prometheid" (Indo-European) — he now reserves "Indo-European” for the Aryan linguistic doctrine, not the language-group — but represents by its “system" a definite stage in linguistic development. Here we have the frequently and forcibly expressed opposition of linguistic palaeontology to comparative-historical linguistics, with the terminological and conceptual antithesis of “system” and “family”. Linguistic relationship is conceived no longer as biological and genetic, but as the historical and sociological integration of a multitude of diverse ethnic languages. This gives the recognised “families” (stocks) the subservient status of links in the chain of the language-building process. Japhetic however is a "system” which is essentially “polystadial,” and so able to illustrate inter alia the history of the grammatical categories — the formal priority of the pronoun, the growth of flexion, the formalisation of spatial and temporal relations. Declension and conjugation are intimately bound up with each other in Japhetic. Numeration, already standardised in the manual (linear) period of speech, with “arm" as the fundamental term taken in three sections (i.e. arm = 1-2, wrist or fist = Z, two fists = 10), reveals in the more “primitive” languages an ancient method of counting, which conceived “many" as three or more. The customary dichotomy of decimal and vigesimal as between Prometheid (Indo-European) and Japhetic is stated to be an unnecessary simplification. Adjective and noun are seen to derive from a common source, the former with a qualitative bias. Plurality represents a later and more advanced notion, because the original emphasis appears to have been on collectivity, out of which the singular was then abstracted by force of contrast. The plural affix was primordially the word for “children" (tribe). As for word

[ 186 ]

symbols of the earlier, matriarchal filiation, they are naturally more in evidence in Japhetic than in Indo-European and Semitic, though these have them too (e.g. Russ, sud’ya, O. Arabic q̇al-ıφaϑun).[33]

Paleontologically Indo-European linguistics is at a disadvantage compared with Japhetic, because it does not command languages illustrating the “primitive" linguistic condition. Indo-European linguistics is necessarily historical, Japhetic — rejecting historicity — palaeontological. Japhetic semantics, for instance, unlike Indo-European, makes less cautious use of association (e.g. by connecting “heaven" — “the nest of protosemes" — with such notions as “head, cloud, luminary, azure, summit, beginning, end, etc."),[34] and being independent of the abstractions of logical association, has often enough nothing to do with that rarefied theorising which Indo-European linguistics anachronistically imposes on prehistoric modes of thought. Japhetic linguistics goes back thousands of years beyond the neolithic and palaeolithic periods,[35] where, exploding monogenesis, it discovers that there never was or could have been an aboriginal phonetic form of speech,[36] although there probably existed a multiplicity of typologically similar ethnic languages, as the curves of their emergence were similar. The phonetic and lexical affinities of later speech, discovered by Indo-European linguistics, appear to have resulted from a long process of hybridisation, of which the Japhetic languages themselves are a striking illustration.IV

In classifying the Caucasian types of Japhetic, Marr adheres to the traditional scheme, detaches North from South Caucasian, i.e. Caucasian proper from Iverian, and proceeds to subdivide the former into an Eastern or Daghestan (Lezginian type), a Central (Chechenian type), and a Western (Circassian type) branch. At the same time North and South Caucasian are effectively segregated according to phonetic criteria,[37] the first, i.e. the mass of Caucasian languages, being allotted to the spirant (A-type) language-group, and the second to the sibilant (s- and s-type). These criteria are preferred to geographical and even typological ones, which Marr ascribes to earlier and presumably obsolete linguistic doctrines. He declares

[ 187 ]

that the separation of North and South Caucasian is "useful only to the formalist,” and that the geography of Caucasian speech is entirely the outcome of historical causes. Using his phonetic criteria, Marr isolates the morphologically unrelated Svanetian and Abkhaz as mixed spirant-sibilant (i.e. h- and s-) types and distinguishes the two as specimens of the hush (š-) and hiss (s-) sibilant allotropes respectively, drawing at the same time a parallel between Svanetian and Basque in this particular. A third, “ sonant ” (i.e. labial-liquid) type is also mentioned, and the three, in a pure state, are said to belong to a very primitive epoch. The residuary Japhetic types had already been hybridised in prehistoric times, and only the still visible linguistic stratification of extant Japhetic can reveal the regular relationship of these ancient phonetic phenomena. Hence the surviving Japhetic types may be described as being only predominantly sibilant, spirant, or sonant, as the case may be. From this standpoint Marr is inclined to dispense with the prevailing geographical-typological classification.V

The consistent application of the palaeontological method to Japhetic revealed to Marr the long perspective of linguistic development and convinced him of the unity of the “ glossogenic ” (he has “glottogonic”) process. At this point he himself began to doubt the validity of including investigation of this process within the already strained limits of the Japhetic theory (yafetidologiya), though he reassured himself with the conviction that the Japhetic languages, as the most “primitive,” obviously offered more abundant material than any other types for the study of the earlier phases of linguistic development. Stimulated by his legitimate misgivings and elaborating the Marxist dogma of the bond between language and thought, Marr embarks on the concluding phase of his linguistic researches, symbolised by the changed name of the Japhetic Institute, viz. the Institute of Language and Thought (1931). We now hear more of the unity of the glossogenic or language-building process, of the equal rights of all the world’s languages (Jakob Grimm did not doubt this, if his successors did), of the prospective evolution of all languages into a common, universal type (this manifestly a reflection of the existing Soviet political order and its revolutionary hopes for the future), and at the same time we hear of the Japhetic theory as "a weapon of the class war,” of “linguistic policy,” and of Leninism (the Russian exegesis of Marxism) as the

[ 188 ]

"arm of Soviet scholarship” In this final phase, which coincides with the last four or five years of Marr’s life, we find, in the linguistic domain, a concentration on semantics rather than the emphasis on phonetics which characterised his earliest and earlier approach, and the typical neglect of morphology, presumably because of its relative newness and perhaps also because of its exaggerated significance in formalist Indo-European scholarship. Semantic (lexical) study by the palaeontological method discloses to the japhetidologist” that diverse languages are more closely connected than the Indo-European School is willing to admit. Indo-European scholarship, according to Marr, treats language groupings as inverted pyramids, the apical "base” representing the monogenetic fiction of the protoglossa, and shows not even a marginal contact between individual pyramids. The Japhetic theory, on the other hand, sees language graphically as a pyramid resting on a broad base, which represents initial multiplicity, as conceived by polygenesis, tending towards an ideal unity. This is more specifically expressed by the symbol of the genealogical tree,[38] which Marr designed in 1926, but abandoned in 1928, because the branches spreading from the trunk suggested too vividly the theory of the protoglossa, which it was his avowed purpose to confute. The genealogical tree however does picture the stages which Marr distinguishes in the language building process, viz. from the roots upwards : (1) the kinetic or linear stage (manual and mimetic language), (2) the tribal or phylogenic stage, (3) the amorphous-synthetic (isolative) stage, (4) the agglutinative stage, and (5) undifferentiated Japhetic speech. The last then constitutes the lower trunk, from which the languages of the Ancient East (primarily Sinitic), Uralo-Altaic (in which Mongolian and Turanian are separated, and Samoyedic is perhaps included in “Finno-Ugrian,” i.e. Uralian), Hamitic, and Semitic diverge as branches. Meanwhile the main trunk reaches upwards into the flexional stage through the remnants of Japhetic. The divergence of Uralo-Altaic takes place through Chuvash, that of Hamitic and Semitic, as of Indo-European, through Japhetic. In the secondary branches, Mongolian, Turanian (Turkic), and Uralian (Finno-Ugrian) are distinguished among agglutinative types, Hamitic and Semitic are given separate growth, and Albanian and Armenian are detached as vestigial from the main stem of Indo-European. The emergence of phonic languages is bound up with

[ 189 ]

the formation of tribes (phylogenesis) and of a social order. Till then language is represented as kinetic or linear, i.e. as a complex of cries, gestures, and mimicry. According to Marr, semantics existed and developed before the appearance of phonic speech, and it was determined by a cosmic philosophy (mirovozzrenie), in which "heaven” and “water,” with the division of the latter into “light” and "darkness,” became the prototypes of the vast majority of words. Another was “hand.” These notions represent the macrocosm and the microcosm respectively, the priority being with the protologos "hand”, the creator of the material culture and the language of humanity.[39]VI

“Mankind created its speech in the process of labour in circumscribed social circumstances and has recreated it with the recrudescence of new forms of living in accordance with new forms of

[ 190 ]

thinking."[40] Changes in the mode of thinking, in Marr's opinion, represent distinct stages, of which the two earliest are the totemic and the cosmic. In studying the totemic mode Marr uses as material the names of peoples and places, because these possess a pre-eminently archaic quality. He considers it possible to reduce the stock of words in human speech to a very small number (say 6-12) of primitive roots or bases, which he at first regarded as exclusively meaningless totemic-tribal names.[41] With the rejection of the predominant role of the ethnos, however, the idea of the tribal origin of primitive word-elements is replaced by that of the “ four fundamental elements," A, B, C, D (or, in the original totemic-tribal conception and terms, Sal, Ber, Yon, Ros). These consist of biconsonantal radicals : A — of a “ lingual " element followed by a " liquid " (l, r), B of a labial also followed by a liquid, C of a lingual or a labial +n, and D of a liquid + a “spirant" + a liquid. None of the four elements is primordial, but they jointly describe the limits of our present knowledge of phonic human speech, and they are the basis of all lexical matter.[42] Their meaning is determined by the social environment, and as this changes, so does their meaning. The four elements have changed their function radically in the course of linguistic evolution and have passed from one system of speech to another. The Japhetic theory assumes that articulate, as opposed to the earlier kinetic speech, is connected with the prevalence of the totemic-cosmic attitude of mind (mirovozzrenie), which characterises the Upper Palaeolithic period. At first articulate phonic speech was closely associated with its kinetic predecessor, and, like this, was simply an active participant in man’s daily concerns, for by that time kinetic speech had passed beyond the initial stage of bodily movements, mimicry, and cries. According to Marr, this would suggest the existence of the thought-process prior to the formation of phonic speech, whose subsequent course was determined by the specific gravity of accumulated knowledge and the momentum of material development. Marr’s emphasis on191 semantics, reflecting the Marxist emphasis on speech as expressed thought, has led him to recognise semantic series (ryady) or clusters (puchki), which figure plainest at the points of linguistic transformation occasioned by shifts in the thought-process. Preliminarily Marr observes that the speech-sounds with which the semantic clusters are associated were originally complex and affricative, as in present-day Caucasian (e.g. Abkhaz), and that they later emerged as words, each original tribe possessing one, i.e. its totem or divine name. The first totem was " heaven,"[43] which at the primitive, “polysemantic ” level stands for a great variety of allied notions, and these are not merely comprehensive (e.g. luminary, bird), but comparative (e.g. mountain, head, top, beginning, end), and accessory or attributive (e.g. blue, tall). The totemic word-clusters belong to Marr’s phylocentric phase of thinking. Later he began to associate his word-meanings with changes in socio-economic grouping. In this way he was able to construct a functional semantics, which stresses not so much the object as its use, e.g., in the word-series covering means of transportation, we have reindeer-dog-horse-cart-boat.[44] With the aid of the palaeontological method Marr penetrates far deeper into language than the structures presented by ancient written monuments and the "class’’ thinking these contain and control, and far deeper than the later logic, producing such seemingly extraordinary clusters as hand-woman- water-tree.

VII

The concept of clusters or semantic series and the four elements describe the periphery of Marr’s linguistic researches, revealing as they do the ultimate reach of his linguistic acumen and of his intuitive and creative imagination. He has left the Japhetic theory behind him and entered the last circle, in which Japhetic speech dissolves into the more primitive beginnings of human expression. That is a sphere of which we have no direct knowledge, and for the exploration of which we have to depend on conjecture.

There is no valid a priori reason for rejecting Marr’s findings, merely because they do not fit into the traditional pattern of Indo- European linguistics. So penetrating a mind as his, for all its human and personal failings, cannot be ignored, and his numerous writings[45]

[192]

deserve the closest scrutiny before they are consigned, whether wholly or in part, to the obscurity of forgotten shelves and theories. Not only was he more alive than anyone else to the legend being woven around him, but he openly disclaimed the linguistic omniscience, of which intemperate admiration wished to make him the living repository. And he was only too conscious of the enormous difficulties confronting him. "It is more difficult to destroy than to create,” he quotes approvingly the words of the vizier to Chosroes I,[46] and in even more disenchanted moments he could descend to the ingenuous humility of his compatriot, the lexicographer S. Orbelian, who wrote in the preface to Qarθuli leqsikoni (1884) : “ Many laugh at these words of mine. If they really love literary works, they will find many such, both divine and profane, and they may read what they have a mind to. But this work is written for ignoramuses like me, so let them leave it in peace.”

[1] Основные таблицы к грамматике древнегрузинского языка.

[2] “Предварительное сообщение о родстве грузинского языка с семитическими.”

[3] V. С. Н. Джанашия, Сборник Руставели (Tbilisi, 1938) ; В. В. Гольцев, Шота Руставели и его время. Сборник статей (Moscow, 1939) ; К. Д. Бальмонт (trans.), Витязь в тигровой шкуре (Moscow, 1936) ; М. S. Wardrop (trans.), The Man in the Panther’s Skin (London, 1912).

[4] V. H. Я. Mapp, “ Яфетидология в Ленинградском Государственном Университете ” (Изв. Лен. Гос. Ун., т. II, Leningrad, 1930).

[5] V. autobiographical note already cited.

[6] Op. cit.

[7] V. “Определение языка второй категории Ахеменидских клиноовразных надписей по данным яфетического языкознания " (Записки Вост. Отд. Русского Арх. Общ., т. XXII, вып. I—II, St. Petersburg, 1914).

[8] E.g. the “Chaldean" of the cuneiform inscriptions at Lake Van in Armenia. V. И. А. Орбели, Археологическая экспедиция 1916-года в Ван (Имп. Русск. Арх. Общ., Petrograd, 1916).

[9] Грамматика чанского (лазского) языка с хрестоматиею и словарем (St. Petersburg, 1910).

[10] V. footnote 7.

[11] “ Кавказоведение и абхазский язык " (Ж. М. Н. П., No. 5, Petrograd, 1916).

[12] Яфетический Кавказ и третий этнический элемент в созидании Средиземноморской культуры (Leipzig, 1920).

[13] Der japhetitische Kaukasus und das dritte ethnische Element im Bildungsprozess der mittellandischen Kultur (Leipzig, 1923).

[14] Sprachfamilien und Sprachenkreise der Erde (Heidelberg, 1926).

[15] V. footnote 4.

[16] V» “ Индо-европейские языки Средиземноморья " (Доклады Ак. Наук, 1924).

[17] V. Чем живет яфетическое языкознание (Petrograd, 1922), in Georgian.

[18] V. footnote 4.

[19] Orient und Occident (Vienna, 1864), p. 535.

[20] “О грамматике литературного грузинского языка”, (ЖМНП, №9, 1873, p. 76.

[21] In 1853 the thought was expressed in German scholarship that “ eine besondere weder indogermanische noch semitische Rasse grosse Gebiete von Vorder- und Kleinasien, Kreta, die Inseln des Agaischen Meeres und auch das Festland von Griechenland bevolkert habe und sich in Europa in den eben schon genannten Volkern fortsetze.” (V. A. Kannengiesser, “ Ist das Etruskische eine hettitische Sprache ?” in Programm des Gymnasiums zu Gelsenkirchen, 1908, p. 4). Marr quotes this passage in " The Japhetic Caucasus " (1920), adding : “ the point of the matter is not in the expression of a general opinion, but in the manner of its formulation… which concretely displays a scientific approach to the question."

[22] V. p. 172.

[23] V. footnote 7.

[24] Нариси з основ нового вчення про язик (Kiev, 1935), pp. 15-24.

[25] V. footnote 11.

[26] V. footnote 12.

[27] Op. cit.

[28] Op. cit.

[29] V. “ Яфетиды " (Boctok I, Petrograd, 1922). This article has been translated into German and Armenian.

[30] V. Актуальные проблемы и очередные задачи яфетической теории " (Изд. Ком. Акад., Moscow, 1929).

[31] The dichotomy of the last two was denied by C. C. Uhlenbeck at the Congress of Basque Studies held in Guernica (Gernika), Spain, in 1922.

[32] Cf. “ Новый поворот в работе по яфетической теории " (Изв. Ак. Наук, Moscow- Leningrad, 19Z1). Here Marr defines Germanic as typologically intermediate between the “synthetic-agglutinative” and “pronominal-flexional” types, with class-indices in process of change into sex-indices. Cf. also F. Braun, Die Urbevölkerung Europas und die Herkunft der Germanen (Leipzig, 1922), where the translator of Der japhetitische Kaukasus studies the Japhetic “ substratum ” of Germanic.

[33] V. “ Яфетические языки " (Большая Сов. Энц., т. 65, Moscow, 1931).

[34] V. “ О ‘ небе ’ как гнезде пра-значений ” (Докл. Ак. Наук, 1924).

[35] V. footnote 30.

[36] V. “ Основные достижения яфетичекой теории " (Rostov-on-Don, reprinted in По этапам развития яфетической теории (Moscow-Leningrad, 192b), р. 246.

[37] V. footnotes 7 and 34.

[38] V. " Über die Entstehung der Sprache " (Unter dem Banner des Marxismus, Heft 3, Moscow, 1926) and the Russian original, “ О происхождении языка ” (in По этапам развития яфетической теории, Moscow-Leningrad, 1926, рр. 286-335), also “К происхождению языков” (in По этапам etc. рр. 278-83).

[39] V. footnote 39.

[40] V. Яфетическая теория (Изд. Вост. Фак. Азервайджанского Гос. Ун., Baku, 1928). For other expositions of the Japhetic theory consult : И. И. Мещанинов, Введение в яфетидологию (Leningrad, 1929), id.,“Яфетическая теория”(Б. Сов. Энц., vol. 65, Moscow, 1931), Н. С. Державин, “ Яфетическая теория акад. Н. Я. Марра” (Научное Слово 1-2, Moscow-Leningrad, 1930), XLV. Академику Н. Я. Марру (Изд. Ак. Наук, Moscow-Leningrad, 1935), Язык и мышление VIII (Изд. Ак. Наук, 19Z7), Памяти Н. Я. Марра, 1864-1934 (Изд. Ак. Наук, 1938), М. Г. Худяков, Сущность и значение яфетидологии (Leningrad).

[41] V. “К вопросу о происхождении племенных названий ' этруски ' и ' пеласги ' (Записки Вост. Отд. Р. Арх. Общ., т. XXV, Petrograd, 1921).

[42] V. И. И. Мещанинов, ‘‘ Яфетическая теория ” (Б. Сов. Энц., vol, 65, Moscow, 1931).

[43] V. footnote 35.

[44] V. Средства передвижения, орудия самозащиты и производства в доистории (Изд. Кавк. Ист.-Арх. Инст., Leningrad, 1926).

[45] Избранные работы Н. Я. Марра, vol. I (ГАИМК, Leningrad, 1933), enumerates (рр. xi-xxvi) 507 items to September, 1933.

[46] V. Ф. А. Розенверг, Хосрой I Ануширван и Карл Великий в легенде (St. Petersburg, 1912).

- Centre de recherches en histoire et épistémologie comparée de la linguistique d'Europe centrale et orientale (CRECLECO) / Université de Lausanne // Научно-исследовательский центр по истории и сравнительной эпистемологии языкознания центральной и восточной Европы