-

- Centre de recherches en histoire et épistémologie comparée de la linguistique d'Europe centrale et orientale (CRECLECO) / Université de Lausanne // Научно-исследовательский центр по истории и сравнительной эпистемологии языкознания центральной и восточной Европы

-- MATTHEWS William Kleesmann : “The Soviet Contribution to Linguistic Thought“, Glasgow: Archivum Linguisticum, 2, 1950, p. 1-23; 97-121.

[1]

"It is impossible to combat physiological transformism with only nomenclature and anatomy.”

Andrej BelyjI

Linguistics in Russia before the Revolution of 1917 exhibits the same fashions and phases of development as in Central and Western Europe and is, to all intents and purposes, a province of European thought open to irradiation from its mainly German “metropolitan” foci. But, as in other intellectual fields, so here, the Russian mind inevitably emerges in its national idiosyncrasy. The originality of pre-revolutionary Russian thinking about language may be gauged by recalling the contributions of a group of academic representatives of general as well as of Russian linguistics, whose activities began in the decade 1870-80. These, not unnaturally, illustrate trends in extra-Russian linguistics, particularly the doctrines of the Neogrammarians and the “conceptualism” of H. Steinthal. The exclusive concentration of the former on Indo-European linguistic material led to an identical scrupulous delimitation of domain in the work of the Russian Formalist School headed by F. F. Fortunatov, and the wider horizons and psychological bias of Steinthal, though not his linguistic typology, may be found reflected in the views of the Khar’kov scholar A. A. Potebnja. Somewhat apart from these, especially in his phonetic preoccupations, stands the Pole Jan Baudouin de Courtenay, who did most of his thinking and writing about language in Russian at Kazan’ and St. Petersburg. Like Potebnja he was hardly a “formalist”, and there is a similar “intuitive” brilliance as well as the reflection of Herbart’s associative psychology (which also, incidentally, influenced Steinthal) in the movement of his ideas. The “formal” and “psychological” modes of approach to language, whose antinomy may be suggested to the European reader by confronting Brugmann’s views with, say, Steinthal’s or, more cogently, with Wundt’s “voluntarism”, received

[2]

their synthesis in the work of A. A. Šachmatov, a pupil of Fortunatov's at Moscow and easily the leading Russian linguist of the "transitional" second decade of the twentieth century. Šachmatov survived into the early years of the Soviet régime, and even to-day his erudite and rather erratic genius, like that of the admired Potebnja[1], is a force in moulding the specialist's views on the history and structure of his mother tongue.

All the linguistic scholars whose names have been mentioned here had at least two things in common, which they also shared with most of their European colleagues, viz., they were primarily historians of language rather than philosophers concerned with extra-temporal abstractions or grammarians intent on exploring and recording contemporary facts, and their sphere of observation was largely confined to the data of Indo-European linguistics, though Šachmatov, at least, showed a serious, if temporary interest in the Uralian Mordvin[2]. Linguistic material outside the Indo-European domain however was being assiduously collected, as it had been earlier in the century by M. A. Castrén and Baron P. Uslar. But the sphere of research was no longer Uralian and North Caucasian, as it had been for the most part with these, but Altaic, especially Turkic, studied by W. Radloff, and Palaeoasiatic, which attracted V. Jochelson and W. Bogoras. Attempts at synthesis in the extra-Indo-European domains were not lacking[3], but they did not result in the compilation of standard comparative grammars, and down to this day, notwithstanding the accession of an immense body of material on all the various linguistic groups of the U.S.S.R., there is no satisfactory counterpart to Brugmann's monumental work on Indo-European.

The background of Soviet linguistics would be incomplete without reference to the early career of a heretical linguistic thinker, who was not taken seriously till after the Revolution and remained relatively obscure in spite of the novelty of his ideas and the erudition of his essays. The predominance and dogmatic authority of the Indo-European School in Russia as

[3]

elsewhere in Europe were challenged in the late eighties by N. J. Marr, the son of a Scotch father and a Georgian mother, who laid the foundations of his Japhetic theory[4] by collating the characteristics of his native Georgian with those of Semitic. This manifestly heterodox equation, whatever its psychological origins and justification may be, was either rebutted or ignored in Indo-European and Semitic linguistic circles both at home and abroad[5], but it did not deter Marr, in the course of some forty years of painstaking enquiry, from raising an imposing edifice of surmise on its insecure foundations. The Japhetic theory in its initial shape implies doubt as to the existence of isolated linguistic structures. Subsequent detailed acquaintance with Armenian led its author to emphasise the process of miscegenation in language[6], and a study of literary Armenian to doubt the structural unity of this language-type. He contrasts the written language of a feudal society with the parallel, but detached development of the spoken language. This is the contrast between, say, Sanskrit and the Prakrits, but Marr widens it beyond a mere dialectal relationship. Further investigation of his mother tongue and its cognates (e.g. Laz or Chan)[7] and of North Caucasian speech, from Abkhaz in the west to Awar types in the east, led him to discover their common denominator, and this enabled him to extend his elastic and expanding Japhetic language-group so as to include all the non-Indo-European and non-Turkic languages of the Caucasus. His classification of these Japhetic languages[8], later reproduced, for instance, by W. Schmidt[9], is still based on the "mono-stadial” comparative method of Indo-European linguistics and

[4]

therefore tacitly recognises the protoglossa, protoethnos, and migration theories, which are part of the Indo-European dogma to this day. Between 1916 and 1930 Marr discovered Vershik (Burushaski) through I. I. Zarubin, studied Basque[10] and the linguistic records of pre-Indo-European "Mediterranean”, and arrived at the exhilarating conclusion that the Japhetic group once extended from the Pyrenees to the Pamirs. By 1920 he had published what is perhaps his magnum opus, and three years later it was to become notorious outside the U.S.S.R. as Der japhetitische Kaukasus und das dritte ethnische Element im Bildungsprozess der mittelländischen Kultur (Leipzig, 1923) in F. Braun's sympathetic translation. This is an outstanding work of brilliant creative fancy, in which Marr’s linguistic, philological, archaeological, and ethnographic studies assume the proportions of a grandiose hypothesis. There is no essential break with the protoglossa theory, though the emphasis is primarily on the “substratum” theory, which was held and popularised in Europe by Hugo Schuchardt. Marr's point of view is still “Caucasocentric”, and he continues to think in terms of "Japhetic”, notwithstanding that its frontiers had by now been considerably enlarged both horizontally and vertically. Up to this point then there has been no rejection of the prevailing linguistic method : Marr is still anchored, though perhaps not so securely as before, in the linguistic past. He was inclined at one time to regard his hypothesis, which incidentally derives from A. Kannengiesser and F. Muller[11], as the turning-point in his mental development. But, as a matter of fact, this was to come later with the impact of Marxism on Soviet linguistics.II

Russian acquaintance with Marxist views goes back to the second half of the nineteenth century, but these exerted no influence on linguistic thought till the twentieth, after the

[5]

Revolution had set up a “Marxist” state in the U.S.S.R. Marx himself had no appreciable interest in language, and his Russian interpreters, notably Lenin, limit themselves to obiter dicta about it. Engels's encyclopaedic mind was drawn to the researches and methods of the Neogrammarians throughout his life, and he had a wide, if not profound, knowledge of various sub-groups of Indo-European, especially Germanic. [12] His views on language were conditioned by his economics and sociology. Language, he believed, was a social “superstructure” erected on a purely economic foundation, and its historical development ran parallel to the vicissitudes of the exploitation of raw materials by human labour. Although a creation and instrument of social intercourse, language in all its diversity is nevertheless not amenable to interpretation in general sociological, and still less in economic, terms. In a letter to Bloch (21st September, 1890) Engels utters a warning against the abuse of the economic exegesis of linguistic data and adduces, as a case in point, the folly of trying to explain the second (High German) sound-shift as the outcome of economic conditions[13]. His salutary warning has unfortunately not been observed by some of his followers, who have tried to force the facts of linguistics into the cramping framework of Marxist dogma. This involves the application of the principles of dialectical materialism to language, and the commencement of the process in the nineteen-twenties may be detected in the writings of linguistic thinkers less original than Marr.

Dialectical materialism[14] is a philosophy of history which borrows from the Hegelian dialectic, classical British economics, and the rationalism of the Utilitarians, and lays particular emphasis on political activism, which gives it a practical bias. It is one of the three main constituents of Marxism, the other two being Marxist economics and Marxist sociology, and it inevitably shares with these the limitations of nineteenth

[6]

century science. From the standpoint of this essay the Hegelian dialectic is the all-important ingredient of dialectical materialism, for it presents that over-simplified triadic scheme of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, which we shall rediscover as a recurrent principle in Soviet historical linguistics. Marx, to be sure, restricted the principle to social and economic history, interpreting this as a spasmodic evolutionary sequence of phases from slave-owning society through feudalism to capitalism, and deriving each phase from its predecessor by the operation of the triadic process. The Marxist, like the Hegelian, dialectic then is dynamic rather then static, diachronic and not synchronic, and the optimism of its author, to whom “synthesis" meant a transcendence as well as a reconciliation of opposites, prefers to view it as progressive. The progressive evolution of matter is conceived as self-generated, and its characteristic attribute of motion as embodying, in Engels's words, the “unity of time and space". Examination of the "laws" governing the dialectical process leads the Marxist, following Engels, to isolate three as fundamental, viz., the transition from quantity to quality, implying transformation, the confrontation of opposites, implying contradiction, and the negation of negation, implying interpenetration and coalescence. Dialectical logic is essentially opposed to formal logic : it is anthropocentric, concrete, and pre-eminently practical. Some of the adjectives used here to delimit the metaphysic of dialectical materialism, viz., “evolutionary" and “anthropocentric", will have suggested its biological or organic character and at the same time its “datedness", which results from its intimate connection with the nineteenth century application of the “ laws " of biology to history and sociology.[15] Hence the exaggerated emphasis on development, with the concomitant explicit criticism of the mechanistic standpoint, hence too the literal translation of such biological ideas as that of the priority of the species to the individual and that of the struggle for existence to the sociological plane.

[7]III

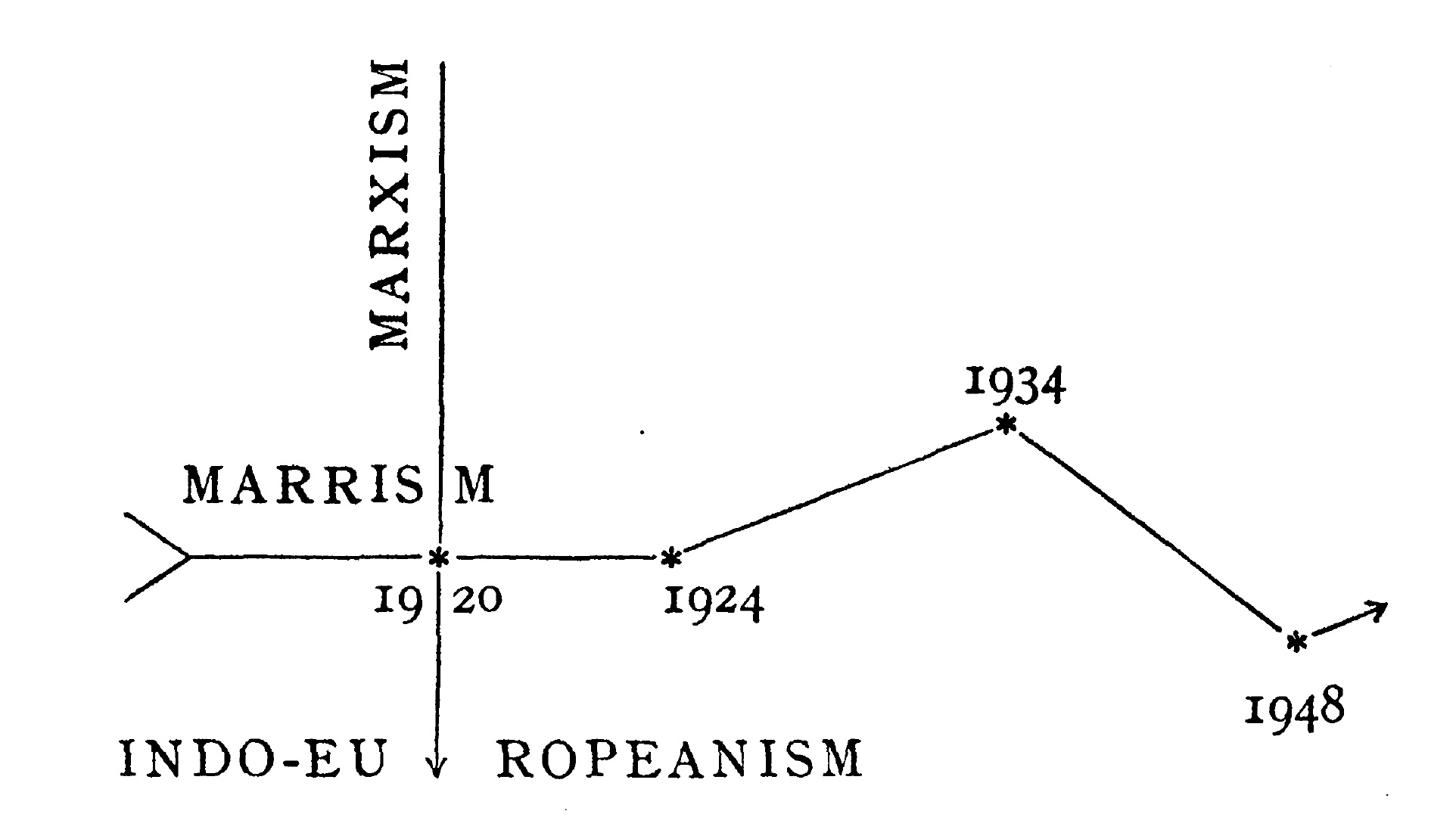

Dialectical materialism in its Leninist interpretation[16], as the official and exclusive philosophy of the Communist (Bolshevik) Party and the Soviet Government, has inevitably influenced all spheres and phases of Soviet thought. Its impingement on linguistics led to attempts in the nineteen-twenties and 'thirties to apply Marxist methods and to promulgate a Marxist theory of language, and of several hybrid types of theory the most imaginative and original — Marr's “new linguistic doctrine” — seems well on the way to becoming the touchstone of Soviet linguistics. A purely Marxist system of linguistics however does not exist, and there is still, as we shall learn later, considerable opposition, both active and passive, to the universal acceptance of Marr’s theory. The evolution of linguistics in the U.S.S.R. may be represented graphically by a transverse line, symbolising Marxism, which bisects a horizontal line, dividing the opposed Indo-European and Marrist schools of thought. The point of intersection indicates the year 1920. Later development follows a zig-zag course, which exhibits an "upward” tendency in favour of Marrist Marxism from about 1924 to the time of Marr's death in 1934, and a subsequent fall till about 1948, when political tension in the world led to the Party-sponsored revival of Marr's doctrine in an “improved” form.

[8]

After 1920 the majority of Soviet linguists remained relatively immune from Marxist influences. D. N. Ušakov's “Short Introduction to the Science of Language” (Kratkoje vvedenije v nauku o jazyke), which had reached its seventh edition by 1925, is a sober and concise exposé of the data of linguistics as free from an extralinguistic “philosophical” bias as, say, J. Marouzeau's contemporary La linguistique, ou Science du Langage (Paris, 1921) ; the study of Russian in all its branches (rusistika) from phonetics to dialectology continued to be pursued in the tradition of Indo-European linguistics, represented at the political turning-point of the Revolution by A. I. Sobolevskij, šachmatov, A. M. Peškovskij, V. A. Bogorodickij, and L. V. Ščerba ; and the accumulation of materials on the languages and linguistic groups of the U.S.S.R. took on a new lease of life, without, in many cases, showing an appreciably different mode of approach from that which had been the rule before the Revolution. Works on linguistic theory, of which several appeared in the U.S.S.R. in the nineteen-twenties, reflect the psychological proclivities of European and American linguistics (e.g. behaviourism) as well as a growing awareness of Marxist theory[17]. By the 'thirties the non-Marxist approach to language had succeeded in effecting a theoretical compromise between Indo-European linguistic method and the socio-economic ideas of Marx. This now appears in Rozalija Šor's lectures and studies, which were later assembled and supplemented by her pupil and collaborator N. S. Čemodanov in their “Introduction to Linguistics” (Vvedenije v jazykovedenije, Moscow, 1945). The late Rozalija Šor was an Indo-Europeanist with a special interest in Sanskrit[18], but she was also attracted to linguistic theory, and her articles are perhaps the first reasoned statement of the Marxist standpoint that is not at the same time Marrist. Her article “Linguistics” (“Jazykovedenije”) in the Major Soviet Encyclopaedia (B.S.E, 65, Moscow, 1931) traces the history of linguistics in and outside the U.S.S.R., and shows how nineteenth century “naturalism” was vigorously attacked in the

[9]

interests of philosophical idealism and a sociological system based on the ideas of Durkheim. There are reflections of the former in Vološinov {op. cit.), but, although the works of Saussure and his French disciples, Meillet and Vendryes, were duly translated into Russian and have exercised an obvious, if specialised, influence on the trends of Indo-European linguistics in the U.S.S.R., they did not give rise to a “sociological" school of thought, as in Switzerland and France, primarily because of the opposition of Marxist doctrine. Unlike Marxism the sociological linguistics of Saussure is content with analysis and “anatomy" and gives insufficient prominence to evolution, which in effect is the synonym of the dialectical process. Schuchardt and Sapir, also carefully studied in the U.S.S.R., have had more influence partly on account of the non-Indo- European materials which inspired and supported their theories, and Schuchardt’s insistence on the primacy of semantics, which, according to Rozalija Šor, showed him to be in advance of his time, found a particularly attentive hearing. The compromise between Indo-European linguistics and Marxism reveals itself even more plainly in Rozalija Šor's other encyclopaedia article “Grammar" (“Grammatika", B.S.E, Vol. 18, Moscow, 1930). This is actually a composite work, its shorter first part written by M. N. Peterson, a pupil of Fortunatov’s and a loyal adherent of formalism, its longer second part by Rozalija Šor, who follows up Peterson's lucid sketch of the history of grammar from Zenodotus to Saussure with a less lucid discussion of the mechanism of grammatical analysis. Rozalija Šor's illustrations are not confined to Indo-European, her treatment is inevitably historical, and her emphasis is on semantics. All this enables her to isolate and view the “units of grammar" as it were “in depth" and against the shifting background of linguistic thought, and to make a tentative classification of the grammatical “disciplines" in terms of the isolated “units". She slightly varies Sapir's terminology to distinguish four kinds of concepts, viz., "radical", “wordforming", “concretely relational", and “purely relational", representing a sort of scale of semantic contractions. Traditional grammar, she says, allocates the first two to the dictionary and retains the last two, viewing them in the interplay of morphological and syntactic form and function. She

[10]

regards it as an error to isolate the “separate word” and to contrast words with word-combinations. In actual fact, she declares with Sapir, we are confronted first of all with the complete utterance and then, as the product of grammatical analysis, with grammatical units. She admits however that “the solution of the problem posed by the objective classification of the grammatical disciplines is manifestly bound up with the solution of the problem of the separate word”.

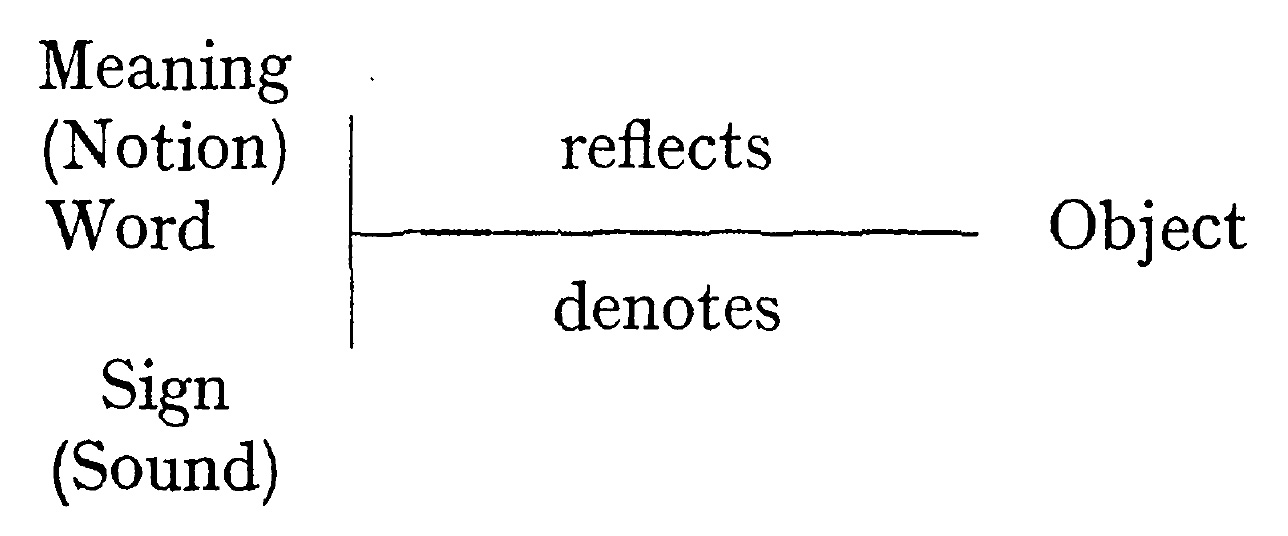

The “central” problem of the word, as distinct from the clearer “marginal” problems of the phoneme and the sentence, still remains open, and until 1948 had not received an entirely satisfactory “dialectical” explanation. As late as 1944-45 it was discussed along mainly non-Marxist lines by Ščerba and his pupil V. V. Vinogradov.[19] On the other hand a “philosophical” and Marxist approach to the problem enables L. O. Reznikov[20] to give a verbal and graphical interpretation of the word in terms of the theory of reflexes. An oversimplified diagram states his argument as follows :

But here we are outside the immediate domain of grammar and vocabulary and must return to Vinogradov’s more “tangible” abstractions. Vinogradov points out the diversity of word-structure in languages of different types and the historically changing interpretation of the category, and suggests the advisability of discriminating between “word” and “lexeme”, defining the latter as a system of forms and functions “perceived against the background of language”. The contrasted domains of word-formation and inflection, an “opposition” peculiar to Russian thinking about grammar, are used to de-

[11]

limit the morphology of the word and of the lexeme respectively. This dichotomy Vinogradov partly inherits from Potebnja, who defined his lexeme semantically as “a combination (sovokupnost) of form and meaning". The other dichotomy emerging from the study of the word, viz., the antithetic spheres of grammar and vocabulary, is also invoked in the course of the exploration of word-forms. Ščerba, whose influence modifies and supplements Potebnja's in Vinogradov's linguistic philosophy, shows his affinity with Saussure by defining the word as a category of "language'' (langue), the system, rather than of “speech” (parole), the realisation, but he partly discounts Saussure’s influence by bringing in Baudouin de Courtenay as having taught the need to avoid confusing various chronological phases in the description of language. True to the prevailing Marxist tendency and the historical tradition in Russian linguistics, of which Marxism may be regarded as the latest expression, Ščerba emphasises the dialectic of language and enjoins this approach on synchronic grammar.

From the study of the word Ščerba proceeds to consider the “semantics'' of its constituent phonetic elements and impinges on the theory of the phoneme, which he took over in outline from Baudouin de Courtenay and the Kazan' School.[21] He had worked out this theory as early as 1912 and had given it an individual stamp by rejecting Baudouin de Courtenay's definition of the concept as psychisches Aequivalent des Sprachlautes[22] and by basing his own definition on a consideration of four principles, viz., (1) awareness of phonetic variety through a limited number of sound-patterns (Lautvorstellungen), (2) differentiation of words by means of phonetic indices, (3) assimilation of various phonetic nuances by “concrete" sounds in the act of recognition without a corresponding change of meaning, and (4) unawareness of the nuances (“allophones") of a phoneme by phonetically untrained speakers.[23] The system of the phoneme is definable in semantic as well as in phonetic terms. Like the word, it belongs to the sphere of “language"

[12]

and, like syntax, is exhibited in "speech”. Ščerba 's definition of the phoneme, as of the word, is sociological and derives from the conception of language as a medium of human intercourse: it deliberately ignores the individual psychological approach, which distinguishes phonetic variety of purely physiological value (e.g. in the Russian words mel “chalk” and mel' “shoal” the differentiation of the vowels is a function of the “opposed” consonantal phonemes l/l’ and is normally unperceived and therefore unphonematic).

Ščerba’s adherence to Marxism in phonetics has not satisfied the orthodox enthusiast. T. P. Lomtev[24] regards his definition of the phoneme as merely a step in the right direction, viz., emancipation from the psychological trammels of Baudouin de Courtenay. It was Marr, according to Lomtev, who introduced the purely Marxist interpretation of the phoneme as “an historically evolved and socially significant speech-unit''. Materialism requires the recognition of speech-sounds as “objective realities”, and the Soviet phonologist is in duty bound to develop his subject along Marrist lines. But Lomtev sees no trace of the influence of Marr, or even of Marx, in the work of contemporary Soviet phonologists. The functional interpretation of the phoneme, which substitutes function for the “liquidated” phoneme, by the Moscow Neophonologists (R. I. Avanesov, P. S. Kuznecov, V. N. Sidorov, and N. F. Jakovlev) is extra-Marxist and reflects the influence of Saussure's and Trubetzkoy's teachings. Trubetzkoy's influence[25], especially in the formulation of the concept of the archiphoneme, has coloured the views of Kuznecov, who uses the term “hyperphoneme”, and of Avanesov, who is content with “phoneme-group”. The Neophonologists then appear to have recovered, perhaps unconsciously, the standpoint of the now dissolved Moscow Linguistic Circle, to which Trubetzkoy's collaborator Roman Jakobson once belonged. Even Ščerba himself[26], if we accept Lomtev's strictures as valid, would seem to have favoured an “idealist” interpretation of the phoneme as against the orthodox materialist one. For him the phoneme

[13]

was a “sound-type”, i.e. an ideal unit, which is realised in the numerous phonematic shades of actual speech.

The three linguistic units — phoneme, word, and sentence — appear to Ščerba as distributed among the disciplines of phonetics, inflection (formoobrazovanije), syntax, and lexicology, the last being a category of Baudouin de Courtenay’s which embodies the “parts of speech” and, through the inclusion of “functional words” (e.g. prepositions, conjunctions, etc.), overlaps with syntax. A simpler classification occurs in Vinogradov’s monumental grammatical study “ The Russian Language ” (Russkij jazyk, Moscow, 1948)[27] and coincides with S. Ullmann’s tripartite division[28], viz., phonetics-lexicology- syntax, but is presumably independent of this, as it first appeared in 1938[29]. The investigation of syntax, which both Ščerba and Vinogradov have so far neglected in the interests of the study of the more minute linguistic “units”, is the domain which was annexed to general linguistics by the pupils of Marr and, indeed, was commended to them by Marr himself[30], to whose post-revolutionary linguistic activities we must now return.IV

Marr had probably familiarised himself with Marxist theory some years before it penetrated into his own, which, as we have seen, was both pre-revolutionary and pre-Marxist in origin. Up to about 1924 he continued to elaborate his Japhetic theory by transforming it from a “Caucasocentric” doctrine to one operating with a multiplicity of languages brought together on extremely slender and often quite fantastic evidence. While his “Japhetic Caucasus” (1920)[31] explained the geographical distribution of the “Japhetic” language-group as the outcome of historical migration, his article “Indo-European Languages

[14]

of the Mediterranean Area” (1924)[32] views it as the result of metamorphosis in situ. This implies a break with the Indo- European theory, which had become his bugbear from the outset of his language studies in St. Petersburg, where, he tells us, the Japhetic theory was born. The break had certain important consequences : it led to a flat denial of the commonly accepted protoglossa theory and the ethnic interpretation of language, and changed the emphasis from linguistic “family” to “system”, which Marr illustrated by presenting Indo-European as a later development of Japhetic. He was able to do this with the aid of his new technique of “palaeontological analysis”, which permitted indulgence in the wildest and most absurd etymologies as well as the expression of remarkable ingenuity in the perverse interpretation of phonetic data (e.g. the recognition of the sibilant-spirant-labial “trinity” and the subdivision of the sibilant series into contrasted “hiss” and “hush” types for use as dialectal criteria). This is particularly evident in the theory of the primordial “four elements” Sal-Ber-Yon-Roš (later A-B-C-D), which, in an articulate phase of linguistic development, occur as components of tribal names (e.g. Sal may be seen in “ Sar-mat-ian ”, Ber in "I-ber-ian”, Yon in “Ion-ic”, Roš in “Et-rusc-an”), and which Marr regards as the source of all existing lexical material.[33] He envisages his palaeontological analysis according to the four elements as something in the nature of physical or chemical analysis.[34] As a typical specimen of it, a follower of Marr’s, L. G. Basindžagjan, who accepts the theory of the four elements with its implications, gives the palaeontological exegesis of the Russian word kogda “when” as ko-g-d-a, where ko- is the relative-interrogative pronoun, -g-d- a hybridised bielemental base meaning “time” (or “heaven” in the archetype), and -a the ending. The -g- and -d- elements, we are assured by the analyst, also occur in Russian god “year”, pogoda “weather”, pogodi “wait”, and in German Gott. Such associations are no less startling than the illustrations of the "logogenic” hybridisation of the “four elements” them-

[15]

selves, for this is the very process by which they have contributed to the multiplication of the world's vocabularies. The combination of the elements A and B (or Sal and Ber in terms of Marr's earlier “tribal" nomenclature) is supposed to present the following parallels, viz., Russian dub “oak", Finnish tammi “oak", Armenian tere “leaves”, which are bound together Indo-European fashion by the formula *tupu (<tu-mu)y and the AC (Sal-Yon) complex is said to be reflected in Basque arte “oak" and Latin arbor.[35] The associations, as will be observed, are simultaneously phonetic and semantic, and insistence on the latter, which is characteristic of Marr, has led to the discovery of “semantic series" [rjady) or “nests" (gnjozda) of words. These may be illustrated from Germanic, which Marr, following certain heterodox German investigators (e.g. S. Feist and especially F. Braun)[36], defines in 1931 as transitional between Japhetic and “Prometheid" (Indo-European).[37] Marr exploits the material of Germanic to trace “ideological” changes by establishing such “horizontal" semantic series, both macrocosmic and microcosmic, as heaven-hill-head-top and such “vertical” ones as heaven-luminary-eye-noble, hill-rock-stone, head-brow, top-to climb, and by ultimately bringing together Stern-Stirn-Stein-steigen. “Heaven" is regarded as the semantic archetype or “protosemantic nest".[38]

Emancipating himself gradually from the association of ethnos with language, which we have seen not only in his acceptance of the Indo-European migration theory, but in the first naming of the four elements, Marr began to seek a new approach to language and ultimately found it in Marx's “stadial" perspective of socio-economic change. He now explains the transition from Japhetic to Indo-European, “the new phase of Japhetic", as due to the invention of agriculture and the discovery of metals.[39] This prepared him for the matur-

[16]

ing Cyclopean vision of a single " glossogenic ” (language- building) process, manifested in the epochs and structures of stadial development, which he defined in terms of a linguistic typology going back ultimately to Steinthal. The original nomenclature of this typology is retained, but it is given a new or “shifted” interpretation : "amorphous-synthetic” (“isolative”), “agglutinative”, and “flexional” are no longer the names of static types, but define the diachronic permutations of linguistic material, representing consecutive phases in the evolution of social consciousness, or, in other words, embody the linguistic reflexes of the triadically conceived “totemic”, “cosmic” (mythological), and “technological” (rational) modes of thinking respectively. The transformation of language, like the transformation of the thought that creates and conditions it, is conceived as a process of hybridisation, which is never complete to its last detail at any given time, i.e. the grammatical structure of a language may simultaneously show the characteristics of more than one linguistic type. This is particularly evident in the languages belonging to Marr’s vast and complicated “Japhetic system”. Marr distinguishes three main branches here, defined in terms of phonetic indices, viz., sibilant (s/š-group), spirant (h-group), and labial-liquid (r/l-group), as well as hybrids of these (e.g. spirant-sibilant), although at the same time he makes it quite clear that the language-systems, of which these are merely discriminatory details, are not determined by isolated indices, but rather by the totality of their formal and semantic features, the emphasis, being primarily on the latter. Nevertheless, Marr certainly uses formal indices, both phonetic and morphological, in the application of his palaeontological method, which he devised and gradually perfected in opposition to the comparative method of Indo-European linguistics, after finally breaking with the latter and adhering to the Marxist conception of the socio-economic basis of speech in the middle nineteen-twenties. Till then, his pupil Meščaninov avers[40], the Soviet contribution to general linguistics had had less to do with theory than with the widening of horizons by the accumulation of fresh materials. This, as we have seen, does not entirely coincide with the stated

[17]

facts, but it does serve to bring out the maturing alliance of Marrism with Marxism.

Through Marr, but not always in conjunction with his own theories, the Marxist historical interpretation of society now began to be applied to language, and this interpretation was sometimes combined with adherence to contemporary West European and American linguistic theories and their underlying psychology or sociology. Marr himself experienced no difficulty in adopting the purely diachronic approach, and its Marxist colouring made his views increasingly popular at home. By 1927 Marxist linguistics on a Marrist basis was firmly established, for not only were the classics of Marxism assiduously studied for their views on language, but Marr's palaeontological method became more and more familiar and even found its way into school text-books in the multitudinous languages of the U.S.S.R. Marr's “new linguistic doctrine" however still continued to be called the Japhetic theory or “Japhetidology", and this is understandable in view of what he himself had to say about it at that time. "Japhetic linguistics", he had written defensively in 1925, “is not Marxism any more than it is a theory, and if it contains principles which confirm the Marxist doctrine, so much the better for it (i.e. the doctrine), in my opinion, and so much the worse for its opponents."[41] Marr remains under the spell of the multiple imposing vistas opening before his linguistic imagination. He already feels that he has discovered the sources of human speech and now confidently propounds a theory of its origin. While admitting the perfectibility of his palaeontological method in the “liberal" Japhetic sense, Marr nevertheless declares that primordial speech was manual and kinetic, and that it presupposes the existence of a developed human brain[42]. These views are partly based on Cushing and Lévy-Bruhl[43], both of whom draw attention to the coexistence of manual and phonic (articulate) expression and go so far as to postulate “manual concepts" (Cushing) and even a grammar of manual speech (Lévy-Bruhl). But Marr arbitrarily introduces diachronic sequence and uses the existence of manual speech among the American and

[18]

Australian aborigines to prove his contention of its priority to phonic speech. This however does not appear to be borne out by existing facts, which suggest that manual speech derives from the diversity and multiplicity of tribal languages in both continents. Whether he was aware of such an alternative or not, Marr is persuaded that phonic speech began considerably later than manual speech, though admittedly in the totemic phase of human culture, and that it first took the form of “diffuse” complexes of sounds, which later assumed the meaning of tribal totem-names, and these, reduced to the “four elements”, ultimately became the lexical basis of articulate speech. Language did not originate in one particular place, but arose and flourished wherever there was a developed social structure with its concomitant ideology. According to the Japhetic theory the origin and evolution of language may be represented diagrammatically by a pyramid resting on its base. With the aid of biological imagery Marr describes the evolution of an infinitude of “molluscoid embryo-languages” by a series of typological transformations into an ideal unity of all the world's languages, which shall reflect the Socialist order of the U.S.S.R. Indo-European linguistic theory, on the contrary, with the protoglossa as its focus, conjures up, in Marr’s view, a pyramid of development poised on its apex.[44] Marr is anxious to enlist the cooperation of other allied sciences — archaeology, philology, ethnography — in his linguistic researches, and insists that his linguistic palaeontology is concerned as much with material as with linguistic data. Absorption in his theory, with its diachronic perspective, repeatedly causes him to retrace the steps by which he arrived at its successive formulations. We find the first account of the phases in the development of “Japhetidology” as early as 1922, when Marr described the fifth and final phase as “palaeontological”, but actually the palaeontological phase, in its characteristic formulation, belongs to 1924 and after. By this time, the Japhetic theory had itself undergone transformation in situ, and the theory of a heterogeneous linguistic system, which had grown by the highhanded annexation of unrelated languages, had become a theory of linguistic origins. As a belated acknowledgement of this

[19]

transformation, the Japhetic Institute of the Academy of Sciences in Leningrad, which had been the centre of Japhetic research for nearly a decade, was renamed the Institute of Language and Thought in 1931, and the four remaining years of Marr's life were devoted to the elaboration of the palaeontological method and of the theory of stadiality (stadial'nost'), which with Marr was based largely on lexical analysis aided by an uninhibited use of phonetic criteria. But Marr realised the significance of syntax in language structure and drew particular attention to the domain of syntactic analysis, which his most gifted follower I. I. Meščaninov has since made his own. Still more, and rightly, Marr insists on all-round, unbiased linguistic study, for “only such study (he assures us) as takes into account all the world's languages can be recognised as the science of language"[45] His unlimited interest in languages was the outcome of his conviction (perhaps a subtle psychological “compensation") of the parity of all languages, great and small, as instruments of expression and objects of study, and of his metaphysical belief in the monism of the language-building process and the common goal of an ideal linguistic unity, towards which, in his view, it appears to be tending. All this is explicit as well as implicit in what he wrote during the “palaeontological" phase of his theory, especially in the nineteen-thirties. “The new linguistic doctrine", as the final metamorphosis of Marr's teaching came to be known, “does not confront the mass speech of emancipated nationalities with the language of megalocratic (Great Power) nationalities, primarily with Russian (says Marr) ; it merely changes the mode of investigating it and in so doing disrupts the pseudo-scientific, ideological principle of the autocracy of Russian".[46] This is all the more true, adds his pupil F. P. Filin[47], as the doctrine has discovered the genetic connection between Russian, “once the instrument of national oppression", and the motley speech of the other Soviet nationalities.

The ideal of ultimate linguistic unity as the reflection of the socio-economic union of the world's peoples would appear to

[20]

be a late development in Marr's doctrine, and its source must be sought in revolutionary Marxism and in the long-term policy of the U.S.S.R.“It may appear strange," writes Stalin[48], that we favour the fusion of national cultures into one common culture (in both form and content), with a single common language, in the future, and at the same time the flowering of national cultures in the present, in the period of the dictatorship of the proletariat. But there is nothing strange in this. National cultures must be given time to develop, to express their latent possibilities, to create the conditions necessary for fusion into one common culture with one common language."

By becoming gradually materialist and Marxist between 1924 and 1930 the Japhetic theory simultaneously became, according to Marr, “a very real weapon of class conflict in the interests of Socialist construction"[49]. In 1930 Marr was already confident that its Marxism was “undoubted". “It has completely fused with Marxism (he wrote) and become part of it."[50] The meeting-point of the two streams of thought, linguistic and sociological, must be sought in their materialist (economic) basis and in their acceptance of the dialectical unity of language and thought and of the conception of language as active consciousness.[51] The fusion of Marrism and Marxism has now been accomplished, and it is Marrism which has had to adapt itself to Marxist philosophy by losing not only its name (Japhetic), but a great many of its earlier characteristic features. It was this fusion that added to the attraction of Marr’s views to Soviet youth, trained in the metaphysics of dialectical materialism, and led to their adoption as the “new linguistic doctrine". “To-day," says Meščaninov significantly, “dialectical materialism is the essential condition of linguistic study."[52]

The influence of Marr's linguistic theory, for all its brief history, has had notable vicissitudes. As the Japhetic theory, based on the identity of language and ethnos and still using the comparative method, which Marr was later to discard for the palaeontological, it had become known to Central and Western

[21]

Europe, and criticism of it had been voiced in the name of Indo-European linguistics chiefly by French scholars, as the upholders of the European tradition. The sober strictures of J. Vendryes in 1924[53] presented sufficient interest to Marr himself, who had the average pre-revolutionary Russian intellectual's sense of inferiority in face of French culture and language, to prompt him to write a detailed rebuttal of the charges made against him, and at the same time to defend the validity of his conjectures, which at this period were focussed in the ethno-linguistic theory of hybridisation. He naturally remains unmoved by his French critic's accusation that his theory contradicts the very principles of Indo-European grammar, and he counters the criticism that his theory rests on a mainly lexical foundation by pointing out that he does not regard words as unique and isolated, but as social facts subject to social laws, which appear in language in the guise of a morphological stratification. The Japhetic theory, Marr concludes, has demonstrated the impossibility of a stable typology like the one on which Indo-European linguistics constructs its dogma. “I know quite well", he ironizes, “that it is difficult for reputable linguists, especially elderly ones, to change their line of scholarship and to start learning afresh." [54]

A similar critical attitude to the Japhetic theory was adopted by the majority of Soviet scholars, who had not found it necessary to abandon the teachings of Indo-European linguistics. These numbered linguists like D. N. Ušakov, M. N. Peterson, and E. D. Polivanov, the last writing as a theorist of Marxism,[55] and historians like M. N. Pokrovskij and V. M. Fritsche, who applauded Marr's materialist bias, but found in his theory “certain not entirely Marxist postulates" (Fritsche) as well as signs of “terminological disorder" (Pokrovskij). There is much less kindness in the youthful strictures of the group of Soviet linguists who styled themselves “The Linguistic Front" (Jazykfront) and largely shared the attitude of the Swedish communist Hannes Sköld.[56] These linguists regarded Marrism as un-Marxist and emanating from the sociology of

[22]

Lévy-Bruhl, and completely rejected the “four elements”. They also attacked the “mechanistic” tendency which they had detected in the palaeontological method as well as Marr's treatment of class in language and his “analytical alphabet”, which they considered to have been devised in the first place for the transcription of Caucasian speech. In this, of course, they were not wrong, and Marr himself was ready to admit the shortcomings of his Latin-Greek-Cyrillic notation, though he believed in its flexibility and adaptability for universal use. Its real defect by the standards of the IPA alphabet would appear to be not so much its localised origin as its reliance on diacritics and a certain inconsistency in their application (e.g. ǧ=[γ], q̇=[x], ṫ=[ts], ď=[dz]).

Among Marxist adherents of Marr’s theory in its later materialist phase, M. Rafail[57] held the view that it required overhauling in the light of dialectical materialism; others, more generous, like A. M. Deborin[58], regarded it as “permeated with a profound internationalism and historicity”, as confirming the principles of dialectical materialism, and as providing a broad foundation for a dialectic of language. All this, to Deborin, emerges from the parallelism between consecutive systems of socio-economic organisation and systems of language, which illustrate the following comprehensive triadic movement : (i) primitive communism, reflected in an amorphous-synthetic structure and a polysemantic vocabulary that does not differentiate “original” from “functional” usage; (2) an economically articulated society, with the beginnings of division of labour and class distinction reflected in speech which distinguishes grammatical categories and “original” from “functional” words, and (3) a class society, with its technological division of labour reflected in a flexional morphology.

Deborin’s attitude to Marr recalls, in some respects, that of his earliest sympathisers in the nineteen-twenties. Marr mentions several of them in his writings. There were the German translator of “The Japhetic Caucasus”, F. Braun, the slavist N. S. Deržavin, who had popularised the Japhetic theory in

[23]

the periodical “Star” (Zvezda)[59], the Ossetic scholar V. B. Tomaševskij, the historian V. V. Struve, and even the linguist Rozalija Šor, whom Marr had once taken to task for connecting his theory with the mechanistic materialism of the eighteenth century.[60] But not one of these was to become a follower in the full sense of this word.

(To be continued)

London

W.K. MATTHEWS[97]

The Soviet Contribution to Linguistic Thought

(Continued)V

Marr's “new linguistic doctrine” has been modified since his death by a group of scholars, who may be truly described as his followers. They are headed by I. I. Meščaninov (b. 1883), lawyer, archaeologist, and orientalist, whose intellectual career has been an extraordinarily chequered one. He began as a student of the history of Russian law at St. Petersburg and continued his law studies at Heidelberg. On his return to St. Petersburg he was attracted to archaeology, attended lectures by Marr, and took up the study of Chaldaean under the stimulus of the Japhetic theory. He was associated with the work of the Japhetic Institute from the outset, taught from 1921 onwards, and became professor at the Leningrad Institute of Modern Oriental Languages ten years later and its director in 1935. Meščaninov turned to general linguistics by first mastering the Japhetic theory in 1926 and found a particular attraction in the theory of stadiality, which he was later to modify and to make his own. His linguistic works include a number of articles on aspects of the Japhetic theory, a study of its relation to Marxism, and a steadily growing series of books on the “new linguistic doctrine”, either in its entirety or in that aspect of it, viz. stadial typology, which appears to absorb his attention most of all.[61] We have already learnt that Marr in his latter days had indicated stadial syntax as a fruitful field of study, seeing that it contained, in Lenin's words, “ all the elements of dialectics”[62]. Marr himself did not live to extend his theory of stadiality to syntax, and it was left to his pupils, chiefly Meščaninov, to do this. According to S. D.

[98]

Katznelson[63], Soviet scholarship has still to succeed in presenting “a complete picture of the stadial development of the sentence”, and Meščaninov, in the opinion of his pupil A. A. Cholodovič[64], has not yet entered on the third and final phase of his theory of stadial syntax, which his two fundamental works General Linguistics (Obščeje jazykoznanije, 1940)[65] and Constituents of the Sentence and Parts of Speech (Členy předloženi]ja i časti reči, 1945) had led his readers to expect. Examination of these works, of his paper “The Problem of Stadiality in the Development of Language” (“Problema stadial'nosti v razvitii jazyka”, Izv. Ak. Nauk, VI, 3, M., 1947), and of his latest book The Verb (Glagol, 1949) will enable us to see how far Marr's theory has been carried by his leading pupil and successor. In General Linguistics Meščaninov accepts Marr’s conception of speech as a complex of utterances (sentences), from which the major parts of speech detach themselves later, the substantive first, and then the verb. As a preface to his investigation of sentence-structures he confronts the traditional with the Marrist divisions of grammar, discovering a “formal rupture” between morphology and syntax in the former and the absence of morphology as an independent category in the latter. The traditional scheme may be seen in Viggo Brøndal's[66] correlation of sound-word-sentence with phonetics-morphology-syntax. In contrast to this, Marrism is “antimorphological”, substituting ”lexicology”, i.e. the theory of the separate word and of word-combinations, for morphology. Here, of course, we have the outcome of emphasis on semantics. “Each word”, says Meščaninov, “has its own definite meaning”, and “there is no word without a meaning.” He distinguishes between the lexical and syntactic aspects of words. Lexical criteria give us the grammatical categories, syntactic criteria the constituents or parts (Meščaninov has “members”) of the sentence, including the primary dichotomy of subject and predicate. The grammatical categories include gender as well as inflections

[99]

(affixes), which in traditional grammar belong to the sphere of morphology, but classifiers (as in Zulu) may be both lexemes and syntaxemes (syntactic elements). Meščaninov draws on the data of diverse language-types to substantiate his findings. The “word-sentence”, for instance, is illustrated from Palaeo-asiatic types like Yukagir (Odul), where we have asajuol-soromoh, “the man saw the reindeer”, lit. “reindeer-seeing- man”, an instance of the “closed semantics” of incorporation and the nuclear function of the predicate. Paramountcy of the predicate may also be seen in Gilyak (Nivkh, Jap. Nikbun), where d’ (t’) is not a verb, but a syntaxeme, indicating predication (vi-d’, “went”, vi-nǝ-d’, “will go”). But Yukagir, we are told, is like Chuckcha (Luoravetlan) in having non-incorporative as well as incorporative sentence-types (e.g. tuŋ köde moni, " this man said”). From the study of incorporation Meščaninov infers that “word and sentence are historical products” and that they are preceded by an “inarticulate condition” of speech, which can still just be caught in the incorporative complexes. After the disruption of the word-sentence the stadial development of speech turns on differences in the semantic and formal interrelations of word and sentence. The fragments of the incorporative complex retain their semantic unity, but assume a different form of concord. One such form is the “nominal” construction of Gilyak, where the verb is not sufficiently in evidence, as it already is, say, in Chukcha and Aleut, and an amorphous-synthetic construction is the general rule. Another form is the possessive construction with the subject of the nomen actionis in the genitive case (cf. Aleut ula-ŋ, “my house”, with suku-ŋ, "I take”, lit. “my taking”). The implication here is that the verb emerges formally out of a combination of nomen actionis and pronoun, and this makes the possessive construction historically earlier than those in which the verb has already been isolated, as in Abkhaz (a North-West Caucasian type), whose verbal system revolves round the dichotomy of transitive and intransitive. A still later departure is the ergative construction, which also derives from this dichotomy. The subject is opposed to the verb in the sentence-complex and discloses two fundamental cases, the absolutive, which it invests where the sentence is semantically intransitive, and the ergative, where the verbal

[100]

notion is transitive. In the ergative construction there is concord between subject and predicate, which is unnecessary in the chronologically earlier sentence-types, e.g. in the possessive, where lack of differentiation between subject and verb provides the “formal” as well as the semantic unity. As illustrations of the ergative construction Meščaninov cites sentences from Chukcha (e.g. kljavol-ja koraŋy tymyr-kyn-en, “by the man the deer killed-he-it”, i.e, “the man killed the deer ”) and from the noun-classifying Dargwa (e.g. adam'-ij vartkel xa-b-uši-b, “by the man the deer it-killed-he”, where b is a classifier). The ergative case of the subject is a sort of instrumental or agentive (cf. the Hindustani preterite construction with the subject defined by the particle ne, viz. magar us ne un se kahā ki Main hūn, “but he said to them : it is I ”, St. John, VI, 20). A transition from the possessive construction to the ergative may be seen in Abkhaz and Lak. A similar transition from the ergative to the nominative is a feature of South Caucasian (Iverian). Before considering this, Meščaninov mentions two other “archaic” sentence-types, viz. the affective, requiring verba sentiendi, and the locative. The first has a passive logical subject (e.g. Georgian mamas ukvars шvili, “to the father to-him-beloved-he son”, lit. “the father loves the son”, where mama-s is dative), whereas in the locative construction the logical subject is a locative attribute of the predicate (e.g. Awar dix ču bugo, “by me horse is”, i.e. “I have a horse” ; cf. Russ, u menja jest’ lošad' and contrast the Awar possessive construction dir ču bugo, “my horse is”, i.e. "I have a horse”). In the affective construction the object, we observe, is in the absolutive case and agrees with the verb. This absolutive case is “neutral”, like the nominative in the Indo-European system, except that the nominative is contrasted with the accusative as the case of the object. In syntactically transitional types of language like Georgian and Laz (Chan), the ergative and the nominative are found side by side, the former expressing the subject of an action, the latter capable of indicating the subject of a condition or state where the verb is either intransitive or passive. The ergative construction is confined in Georgian to the aorist, while the nominative is associated with the present tense and the affective with the perfect, but in the “more primitive” Laz the ergative construction

[101]

occurs in all tenses of the transitive verb. The nominative construction with its emphasis on the individual as the doer of an action represents a change in the “norms of consciousness", but the linguistic material comes to it from earlier sources. It is in effect a metamorphosis of the ergative construction.

Investigation of the parts of the sentence leads Meščaninov, at the end of his book, to focus attention on the changing relationship of the grammatical categories to these. This subject also occupies him in his next work, Constituents of the Sentence and Parts of Speech (1945), where, after examining the formal and syntactic methods of expressing syntactic relations, Meščaninov attempts to trace the origin of the parts of speech. His syntactic analysis is based, as elsewhere in his work, on the material provided by languages of diverse typology, and its results may be summarised as follows : (1) complete incorporation characterises the sentence, partial incorporation its inner articulation; (2) synthesis and concord illustrate a similar parallelism at a later period ; (3) “disjunction" defines those parts of the sentence which are isolated, government the words dependent on others ; (4) word-order (relative position) covers all the words in the sentence, “adjunction" (primykanije) is peculiar to their particular relationships; and (5) intonation extends over the entire sentence, whereas its syntagmas pick out its components. Meščaninov distinguishes several degrees of incorporation and illustrates them with sentences from the various Palaeoasiatic language-types. Synthesis is expressed by classifiers (class-indices) and prevails in the North Caucasian languages. Concord in Indo-European is a vestige of it. “Adjunction", seen, for instance, in the Semitic “construct state", differs from concord in being purely semantic, and may be illustrated by the placing of the qualifier before the qualified word in agglutinative languages. “Disjunction" (isolation) also involves the semantic independence of the words isolated. The remaining terms which Meščaninov uses explain themselves.

Inside the “articulate" sentence Meščaninov distinguishes both primary and secondary groupings (syntagmas). The major dichotomy, as we have already indicated, is that of subject and predicate. The secondary “members" comprise the

[102]

direct object as well as other complements and the adverbial extensions of the predicate. The number and character of the parts of the sentence differ from one language to another. Thus “primitive” language-types are characterised by asyndeton and a dearth of relatives, while Altaic, especially its Turkic branch, has participial epitomes of semantically complete clauses. Syntactic function, says Meščaninov, is the basis of the differentiation of grammatical categories as well as of parts of sentences. The former illustrate the morphological “fixation” of this function, i.e. they constitute a system of recognising grammatical forms. On the other hand the parts of the sentence, for instance subject and predicate, are wider grammatical categories expressing corresponding notional (ponjatijnyje) categories, which Meščaninov is able to differentiate by reserving the Latin terms “subject” and “predicate” for the latter and the more concrete Russian podležaščeje and skazujemoje for their “materialisations” in the former.

The progressive limitation of domain characteristic of Meščaninov’s writings since 1936 has reached a climax in his study of the verbal category (The Verb, 1949), which we may appropriately consider out of its chronological order at this point. Although the general trend of his researches remains diachronic, and although the diachronic standpoint still obtrudes on occasion to present linguistic facts “in perspective”, his latest book is largely a synchronic analysis of diverse types of predicate — incorporative, agglutinative, flexional — and an attempt to isolate the verbal concept from these constructions. He draws a scrupulous distinction between predicate and verb, lists the grammatical categories of the latter, and shows the priority of mood and voice to tense, aspect, and person as verbal indices, and the importance of the transitive-intransitive antinomy in aiding the crystallisation of the verb. Semantic as well as formal indices are considered in detail, and a complex word-picture of this most important part of speech is assembled out of the material drawn from an impressive array of sources, which include extra-Soviet as well as Soviet languages, Zulu and Nemepu (in British Columbia), French and German, as well as Yurak Samoyedic (Nenets) and Chukcha, Aleut and Adyge, Kazakh and Russian.

The latest phase of Meščaninov’s theory of stadiality is

[103]

represented by his article "The Problem of Stadiality in the Development of Language” (1947), which halts on the threshold of a synthesis of its first two phases, viz. the statement of the thesis of stadial development in terms of syntax in General Linguistics and the systematisation of sentence-structure in Constituents of the Sentence and Parts of Speech (1945). Meščaninov looks back and calls for a review of the entire question of the relationship of subject and object, which is fundamental to the syntactic aspect of stadiality. “The structure of a language”, he tells us, “is the sum of its grammatical indices (morphology) and its principal grammatical constructions (syntax).” "Construction” (stroj) and “stage of development” (stadija) need not be synonymous: "if they were, modern Georgian would be found to be simultaneously in three stages of development.” Differences in the syntactic structure of various languages, for instance between the possessive, ergative, and nominative constructions, are purely formal. This is the synchronic view. On the other hand, the rise of these “historically” divergent forms of syntax is associated with semantic changes, i.e. with shifts in social “ideology”. The syntactic function of the various constructions, however, remains the same ; it is only the form that is different. Meščaninov discovers this in such languages as have a traditional literary pattern, and particularly in the adaptation of traditional constructions to new uses in the newly literate languages (mladopis'mennyje jazyki) of the U.S.S.R. The conclusion of his article is that the semantic aspect of language, the creator of its syntactic structure, is in a dialectical relationship with the formal aspect, which it conditions ; that the stages of development may be “polysystematic” (multi-structural) ; and that only the history of a language based on authentic and carefully sifted material can supply the data needed to establish its stage of development. Reviewing these conclusions, Cholodovič (op. cit.) recognises the presence of doubt and hesitation in Meščaninov's thought and suggests that these inward obstacles may be overcome by discriminating between "stage of development” [stadija) and “construction” [stroj). The difficulty lies obviously in the arbitrary selection of linguistic criteria to describe an arbitrarily defined evolutionary movement (dialectic) and in the confusion of synchronic and diachronic data. Hence the differences of opinion

[104]

with regard to the priority of the various syntactic constructions in the historical scheme. Some investigators, including Meščaninov himself, consider the nominative construction to be derived from the decomposition of the ergative ; others, for instance D. V. Bubrich, think that the nominative and ergative constructions represent two parallel developments out of an earlier “absolutive" construction. Such differences, says Cholodovič, attempting to reconcile them, are “technical" and not "ideological", because “on the ideological plane there can be only one trend". He would, no doubt, be more inclined to agree with M. M. Huchman[67], whose analysis of the nominative construction of the Indo-European sentence, with its correlation of predicate and verb, reveals traces of pre-nominative relationships (e.g. emphasis on the object in constructions with the dative or the accusative of the person : Lat. mihi placet, O. Isl. mik lystir til, “I have a fancy for", Russ, mne chočetsja, “I want") and prompts him to infer that these probably derive from a stage of development which was also not homogeneous syntactically.

These and other representatives of the theory of stadiality in the U.S.S.R. may differ among themselves on points of detail, but they all accept its general principles if they have come within the orbit of Marr’s influence. Opposition to it comes largely from the Indo-European camp both at home and abroad. Among non-Soviet scholars who have criticised the theory is the Pole Jerzy Kurylowicz, whose strictures have appeared even in the U.S.S.R.[68] He justly regards the scheme of stadial development as a combination of the Hegelian (Marxist) dialectic with a series of linguistic phenomena arbitrarily, and no doubt erroneously, invoked as peculiar to “primitive" language (e.g. the inclusive and exclusive plural forms, which have their counterpart in Indo-European, say French nous/nous autres). Modern linguistics certainly knows of no languages with a more “primitive" structure than others, unless one confounds “structure" with “level of material culture", which, incidentally, admits of regression as

[105]

well as of progression. Adopting the self-centred, abstractly synchronic point of view characteristic of present-day West European linguistics, Kurylowicz demands that linguistic exegesis should be “immanent" and not in “allogeneous" terms, i.e. that language should explain itself without resorting to the aid of other disciplines, and denies the stadial development of human thought and of its linguistic medium by proving the “semantic" differences between the ergative and the nominative constructions to be limited and merely “stylistic”.VI

If the development of linguistics in the U.S.S.R. may be conceived in terms of a musical pattern, the beginning of its latest "movement" is cacophonous and violent. This assumes the form of a recriminatory debate, which followed the reading of two papers — Meščaninov's “The Situation in Linguistic Science" and F. P. Filin's “Two Trends in Linguistics"[69] — at an open joint session of the Council of the Marr Institute of Language and the Leningrad Branch of the Russian Language Institute on the 22nd of October, 1948. The papers appear to have been inspired by T. D. Lysenko's on the position of biology in the U.S.S.R., which was read before the Lenin Agricultural Academy earlier in the same year. Meščaninov dwells on the fundamental opposition of the Marxist and the Formalist school of linguistics and the inadequacy of the latter's ideas to Soviet scholarship, with its preponderantly historical and Marxist vision, and makes a plea for the general acceptance of Marr's doctrine in its closing phase. He records the vicissitudes in the development of Marr's linguistic thinking and shows how his followers, starting from the point at which he had left off, abandoned the hypothesis of the four elements and concentrated on stadiality in terms of syntax. In the course of his paper Meščaninov merely mentions the names of opponents and dissentients, but his younger colleague Filin attacks them in an impassioned and polemical defence of Marrism. In Filin's view this is politically “an organic component of the ideology of a socialist (he means ‘Soviet') society", and he rejects the

[106]

Indo-European theory of the protoglossa which, he alleges, “was used for their own ends by the German fascists” and “is now being used by the Anglo-American aggressors”. He makes V. V. Vinogradov the butt of an attack, taunting him on the showing of his recent article “Literary Russian in the Researches of A. A. Šachmatov”[70], with pro-Šachmatov “idealism", the cultivation of the Indo-European comparative method, and “a servile imitation of West European linguists and a leaning towards them”. He also mentions as hostile to Marrism the views of R. I. Avanesov, V. N. Sidorov, P. S. Kuznecov, L. A. Bulachovskij, and M. N. Peterson, and asks in what way the phonological studies of the first three differ from those of Trubetzkoy and R. Jakobson. Marr’s doctrine, says Filin, has been minimised by attempts to restrict it in a variety of ways, and it is positively harmful to say that it has been completely forgotten since he died. It is not enough, he proceeds, to pay mere lip-service to Marr; “one must become his follower and champion."

The political animus of Filin’s paper stirred the many linguists present at the meeting and divided them into two camps, the Marrist and the Formalist, the latter of which visibly shrank in numbers as the debate proceeded.[71] Je. S. Istrina complained of the lack of “a united linguistic front” in the U.S.S.R. ; N. P. Grinkova laid the blame for the widespread indifference to Marr on the “feeble” Marrist propaganda of the directorate of the Marr Institute of Language and Thought; B. A. Larin complained that the “new linguistic doctrine” had not influenced specifically Russian linguistics and accused its representatives, Avanesov, Bulachovskij, and Vinogradov, of “triviality” and “superficiality” ; S. D. Katznelson traced the hostility to Marr to G. O. Vinokur, who in 1941 had defended Saussure and the protoglossa; the Romance scholar V. F. Šišmarjov pointed out the neglect of Marr’s doctrine “as an ideological weapon’’ ; A. D. Rudnev said that formalism still dominated the schools, because school text-books had not broken with its traditions and were content to follow Peškovskij, Ušakov, and Peterson, and that a forma-

[107]

list attitude characterised the pedagogical journal Russian in School (Russkij jazyk v škole) ; Je. M. Galkina-Fedoruk regretted that university students still relied on Leskien, Sobolevskij, and Kul'bakin ; and M. M. Huchman stigmatised the Moscow centres of higher education as the hot-beds of anti-Marrist propaganda. Various books, for instance L. P. Jakubinskij's The Formation of Peoples and their Languages (Obrazovanije narodnostej i ich jazykov), L. I. Žirkov’s Linguistic Dictionary (Lingvističeskij slovar'), G. O. Vinokur's The Russian Language (Russkij jazyk), and the histories of English, French, and German by B. A. Il'jiš, M. V. Sergijevskij, and L. R. Zinder and T. V. Strojeva respectively, as well as recent articles by Vinogradov, Avanesov, and Istrina, and the regulations (postanovlenija) of the Moscow University Russian Department[72], which even in 1947 had recommended consultation of the works of Saussure and other non-Soviet scholars, although their standpoint was anti-Marxist, are all singled out for special censure. But the most remarkable incident in the stormy debate began unceremoniously with Ju. S. Maslov's invitation to those present to admit and recant their errors, because the development of linguistics in the U.S.S.R. required "complete divorce from bourgeois science" both at home and in the West. There could not be two Soviet linguistic schools, Maslov said, and Marr's doctrine was the only acceptable one. A superficial adherence to it, he thought, was not enough : Vinogradov's recent quotations from Marr had failed to conceal his fundamentally non-Marxist approach. A. V. Desnickaja, a belated convert from Indo-European orthodoxy and now secretary of the Communist group at the Marr Institute of Language and Thought, refrained from “personalities", but drew attention to the growth of the spirit of compromise and complacency among Soviet linguists and insisted on “the severest criticism of the influence of bourgeois linguistics" on its Soviet counterpart. One after another linguists at the meeting, beginning with V. V. Žirmunskij, rose and openly admitted their errors. Similar recantations were made by Vinogradov, Avanesov, and others at a joint meeting of the Council of the Russian Language Institute and of the Moscow Branch of the Marr Institute of Language and Thought in Moscow in the

[108]

autumn of 1948,[73] but Peterson charged Marr's followers with being dogmatic and Marr himself with having committed “many blunders”, and Kuznecov stubbornly defended the protoglossa theory. O. I. Moskal'skaja was not satisfied with the recantations and acidly accused those who had made them of a “semi-admission of error”. The meeting was wound up by Meščaninov, who declared, as he had already done at a joint meeting of the Institutes two years before[74], that dialectical materialism must in future be the foundation of Soviet linguistics, and the Council of the two bodies, in its resolution, urged on their directorates the paramount need of consultation with the Bureau of Party Organisation about the course to be taken “to destroy reactionary idealist linguistics” and to further “the creative development of the new linguistic doctrine”.

It is obvious from the foregoing, more especially from Filin's explicit reference to “Anglo-American aggressors” in his paper, that Soviet linguistics, like other fields of Soviet intellectual activity, has been exposed to the political bias of the hour, and that strong pressure has been exerted on the recalcitrant and the indifferent to make them aware of the ”Party line”. Perhaps the most striking effect of the political distortion of linguistic thinking thus far is to be found not so much in Žirmunskij's reference to “the fatuous and sorry attempts of Anglo-American philosophers, psychologists, and linguists to overthrow the foundations of Marxist linguistics”[75], as in the review of Sturtevant’s An Introduction to Linguistic Science (New Haven, 1947) by A. V. Desnickaja.[76] What Soviet linguistics is not, we may gather from the closing paragraphs of this review. “The work of American linguists (we read there) in the investigation of the world's languages is closely bound up with the aggressive designs of American imperialism on the peoples speaking them.” What follows is even more pointed.

“Theoretical' work in the linguistic sphere (she says) is also

[109]

being pursued in the interests of reactionary ideology. All the forces of obscurantism and reaction have been recruited for the struggle against Marxism. The biologisation of social phenomena, the reduction of human consciousness to the animal level, the assertion of the elemental and immanent nature of linguistic development, agnosticism, the idealistic theory of linguistic signs, the formal-genetic theory of linguistic development (the protoglossa conception of ‘relationship') — such is the ideological stock-in-trade of linguistics in the service of American imperialism."

These repercussions were some of the immediate effects of directives issued by the Communist (Bolshevik) Party to the whole body of Soviet linguists. Later repercussions are connected with the impression produced by an address, which was given by V. M. Molotov on the occasion of the 31st anniversary of the Revolution, and more particularly by N. Bernikov and I. Braginskij’s article “For a Progressive Soviet Linguistics" (“Za peredovoje sovetskoje jazykoznanije"), which appeared in Culture and Life (Kul'tura i žizn’), the organ of the Propaganda Department of the Central Committee of the Party, on the 11th of May, 1949. Molotov's reference to “the creative significance of the materialist principle" was taken by G. P. Serdjučenko as the starting-point of his article “For the Further Advancement of the New Materialist Linguistic Doctrine"[77], which echoes that of Bernikov and Braginskij. Serdjučenko admits that the British Member of Parliament, who, in a letter to The Times (24/VI/1929), had complained that Marr's doctrine was “a mouthpiece of Bolshevism", was "not far from the truth", and he proceeds to list its abiding elements, which include stadiality, functional semantics, and the emphasis on national idiosyncrasy, but not the discredited theory of the four elements or the dubious role of magic in language. Marr's followers, Meščaninov among them, have tended to overstress the comparative and formal side of linguistics to the detriment of the historical, and the undeniable value of the systematic grammatical study of Soviet languages, to which most of them have contributed, is diminished by the lack of a uniform mode of treatment (e.g. Dmitrijev's

[110]

traditional presentation of the facts of Bashkir grammar begins with sounds and ends with syntax, whereas Jakovlev's treatment of Kabardin reverses the order of the sections)[78]. Soviet linguistics, which, according to Serdjučenko, still suffers from the “liberal” attitude of compromise and is not free from "reactionary idealism", takes inadequate interest in the requirements of the national languages and is insufficiently aware of its own practical applications. It is curious that not only Žirmunskij is singled out as an offender, but also his pupil Desnickaja, who is accused, as she was by Bernikov and Braginskij of trying to combine materialist principles with those of West European linguistics. Both of them have apparently shown partiality to Jespersen’s “chauvinistic” idea of the superiority of the “analytical" language-type (e.g. English) to the “synthetic” Russian type. The impact of the Bernikov-Braginskij article led to two meetings of the Marr Institute of Language and Thought. The first was held in Moscow on the 27th and 28th of May, 1949, the second in Leningrad on the 28th and 29th of June. At both meetings resolutions were passed commending the standpoint and strictures of the authors of the article, who complained that Soviet linguistic theory had not kept pace with developments in the Soviet national languages and that not all the members of the “reactionary idealist” group of scholars, for instance Peterson, Kuznecov, and Sidorov, had admitted their errors. The resolutions also voiced the need of completing a definitive edition of Marr’s writings and the publication of a vade-mecum of his views on linguistic problems, as well as of another giving those of the classics of Marxism.[79]VII

The Soviet contribution to linguistic thought may now be examined as a mostly synchronic inventory. This will probably be found to consist of some ten different items, covering the entire field of linguistics and emphasising certain aspects, in which we have already discovered elements of materialism and

[111]

monism, history and dialectics, Marr and Marxism. The most striking and probably the least enduring contribution is that of Marr, who looms large in the history of Soviet linguistics and is regarded by some as its founder[80]. Part of Marr's contribution results from a fundamental opposition, stated polemically, to the prevailing Indo-European linguistic dogma, the “thesis" to the “antithesis" of the Japhetic theory and its metamorphosis, the “new linguistic doctrine". This opposition derives, to some extent, from a difference of emphasis : Indo-European linguistics is mainly "comparative" and “ethnic" (the Marrist would say “racial") ; Japhetic linguistics is "historical" and "socio-economic". The difference between the two irreconcilable theories grows perceptibly more acute with Marr's elaboration of the “palaeontological" method, which, as we have seen, operates exclusively with lexical and etymological criteria and in its fantastic absurdity is utterly unacceptable to the Indo-European comparative technique. On a purely practical level the palaeontological method expresses itself in the use of Marr's “analytical alphabet" with its “poly-phonematic" Caucasian basis. This offers nothing new in the classification of sounds, but its interest lies in what it includes and accentuates and how it names. The vocalic- consonantal antithesis is accepted and the semivowels are taken as bridging it. Great importance attaches to sound attributes or “technical media" (the Americans' “suprasegmental phonemes"), notably duration, nasal resonance, stress, and tone. The terms “hard" and “soft", inherited from the conventions of Russian grammar, and “strong" and “weak", which point a morphological contrast found in Germanic, are used to discriminate between vowels and consonants respectively. Thus the peripheral i/e, a, and o/u are “hard", the centripetal ä, ö, and ü are “soft" ; the plosives and most fricatives are “strong", the sibilants and semivowels "weak".