[1] E. D. Durrant, The Language Problem, Its History and Solution, (Heronsgate, Rickmansworth, Hertz, England, 1943), p. 49.

[4] Albert L. Guerard, A Short History of the International Language Movement (New York, 1921, p. 218. Guerard gives a sample of Nepo. In the Lord's Prayer following, German words are indicated by an asterisk (*); English by two (**); Russian by three (***), Esperanto and French by no sign: “Vatero* nia, kotoryja (***) estas in la njeboo (***); heiliga (*) estu nomo via, kommenu (**) regneo via, estu volonteo via jakoe (***) in (**) la njeboo (***), ebene (*) soe (*) na (***) la erdeo (**)." There could not have been many imprints of the system, for the very complete international language library presently in the New York Public Library, contains nothing on either system.

[5] Leon Trotsky, Stalin (New York, 1941), p. 118, quoted in J. Kuchera, “Linguistic Policy of the Soviet Union”, (Dissertation), Harvard University (Cambridge, Mass, 1950, p. 333-4.

[10] H. Jacob, A Planned Auxiliary Language (London, 1947), pp 125-6.

[12] B. Grande, "Jazyki Narodov SSSR," Bolshaya Sovietskaya Entzyklopedia (Reprint, Baltimore, Md., 1949), coIumns 1625-26.

[13] Cf. Kuchera, Chapter VI.

[14] B. Grande, col. 1627 et seq.

[18] V. Chaplenko, in a personal letter to the writer, dated July 25, 1954.

[19] Cf. Kuchera, pp. 211, 273-6, 280-3. The subsequent elimination of philologist Marr did not, apparently, change Soviet philologic science in this respect.

[20] P. Kovalik, consultant of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the United States, in a personal letter to the writer, dated July 25, 1954.

[22] B. Grande, col. 1630.

[23] Article in Time. LV (March 27, 1950, 29.

[24] H. Lalich. The Russian Language and Great Russian Chauvinism. (New York. 1950, pp. 4-5.

[25] Julius Dolanský, "Cím nám byla a je ruština," Slovanský přehled (Prague, 1949), p. 23, quoted in Kuchera, p. 326.

[27] M. A. Pei, "Conquest of Babel?" New York Times (May 24 1953), pp. 42-44 Professor Pei suggests that the entire solution to the problem lies in the mutual acceptance by Russia and the rest of the world of English transliterated into Cyrillic. For those sounds in English which cannot be phonetically transliterated, Professor Pei suggests the use of certain letters appearing in the Serbo-Croatian alphabet. He suggests that this might be acceptable to the Russians since the national and international English would be two different tongues. He feels that Russia would have "the satisfaction of having contributed to the world tongue its written form," in the light of what is here presented it would seem that Professor Pei has been guilty, in this case, of some rather wooly thinking. Just as conceivably, one might suggest transliterating Russian into Homan orthography for world use!

[28] W. Churchill, (“Alliance with the United States After the War"): address at Harvard University, September 6, 1943, quoted in Vital Speeches of Today. IX (September, 1943), 715.

[29] J. V. Stalin In "Intervyu Tovarishcha I. V. Stalina s korrespondentom Pravdy otnocityelno rechi Gospodina Churchilla 13 Marta 1946 Goda," Gospolitizdat. 1946, pp. 4-5, quoted by Jartseva, p. 18.

[30] V. N. Jartseva Reaktsionnaia Sushchnost Teorii Mirovogo Anglo-saksonskogo yazyka ("The Reactionary Substance of the ‘World Theory' Anglo-Saxon Language") (Moscow, 1949). It is sub-titled in Russian, "A stenograph of a public lecture given the 23rd of April, 1949, in the Central Lecture Hall of the Society in Moscow by Doctor of Philological Sciences, Professor V. N. Jartseva: The All-Union Society for the Dissemination of Political and Scientific Knowledge," It was printed by the Pravda Publishing House, Moscow.

[32] Jartseva, cf. pp. 11-13.

[33] Jartseva, pp. 15-16.

[36] Kuchera, cf. pp. 333-5.

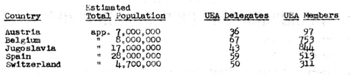

[37] The term "delegate" as used here may be misleading. Page 95 of the Jarlibro (Yearbook) of the Universal Esperanto Association sets forth that ”anyone may become a "delegate" by being of 21 years of age, an Esperantist, and a membro-abonarto (such membership costing about three dollars a year), and by applying for such delegacy, Membership in the UEA is obtainable on the subscription of approximately one dollar and twenty-five cents. The economic conditions of the country listed, as well as the ability or inability to receive a British-published journal, would doubtless be modifying factors in evaluation of the figures here given.

[38] Figures given ere from The Statesman’s Yearbook of 1954, and are in round numbers. / cf. Jarlibro, 1954: Universale Esperanto Asocio, Unua Parto, (Heronsgate, Rickmansworth, England), pp. 101-255. V. n. 37 supra. / Cf. Jarlibro, 1954: Universale Esperanto Asocio, Dua Parto, (Heronsgate, Rickmansworth, England), pp. 8-10.s V.n. 37 supra.

[39] Cf. Jarlibro, 1954. Unua Parto, pp.167-180. V.n. 37 supra.

[40] "Esperanto in Action”, Amerika Esperantisto, LXVIII (May-June, 1954), 35.

[41] Progreso. (January-march, 1954), (p. ii).

[42] Cosmoglotta, XXXIII (May-June, 1954), p. 32.

[43] E. Lienhard, "Allgemeine Orientierung ueber die heutige Situation in der Weltsprachenbewegung," Interlingue-Novas. (November, 1954), (p. 1.)

-- Edward F. JAMES* : «Soviet Linguistic Policy and the International Language Movement», The International Language Review, vol. 1, n° 1, 1955. (no page)