-

- Centre de recherches en histoire et épistémologie comparée de la linguistique d'Europe centrale et orientale (CRECLECO) / Université de Lausanne // Научно-исследовательский центр по истории и сравнительной эпистемологии языкознания центральной и восточной Европы

-- Ludwig Noiré : The Origin and Philosophy of Language, 2nd Edition Revised and Enlarged, Chicago – London : The Open Court Publishing Company, 1917.

CONTENTS

1. The Origin of Language 1 2. The Logos Theory 37 3. The Origin of Reason 49 4. Darwin and Max Müller 61 5. Max Müller and the Doctrine of Development 75 6. Speech and Reason 90 7. Max Müller and the Problem of the Origin of Language 107 8. Noire's Theory of the Origin of Language 128 Index 157 [37]

2/ The Logos Theory.The designation which I wish to give to my theory of the origin of language is the Logos Theory. Two other designations, the Sympathy Theory, and the Causality Theory, may, perhaps, also be suitable; but they are incomplete, as they only embrace certain single parts of the organic analysis with which we have to deal. The Logos Theory, on the contrary, fixes the centre of gravity of the question at the very point where it must be sought—namely, in the origin of the concept and in the union of the various contrary things that had to meet and organically combine, in order that human speech and thought—the greatest of miracles, and the pride of creation—might arise and be developed. The Mimetic and Interjectional theories of language are explanations of thought that appeal to such people only as do not think.

I shall start, in the present investigation, from a comparison of language with poetry.

Poetry, even at the present day, is essentially a creation of language, that is, a creation of concepts. And, so, too, all primitive creation of language was poetry—lofty, ideal poetry. When, amidst the discordant, noisy, many-voiced choir of utterances indicative of will and sensation, there was heard, for the first time on earth, a sound that conveyed a clear, intelligible sense, an objective meaning, that sound

[38]

signalised a moment replete with sublimest poetry— for then dawned the sixth day of the creation of the world.

Examining the method of poetical utterance, we find that external always acts upon external. This relation, which is one of cause and effect, is the fundamental rule of all cognition and comprehension of the perceptible world. Everything must be referred to this principle; through it all must be expressed; without it no utterance is possible. In all the following examples, therefore, it must be tacitly assumed; because, manifestly, whatever is internal as regards speech and thinking, actually exists only when it attains to expression, that is, when an external phenomenon is offered that strikes the senses. This first category, accordingly, of the four which I assume,[1] is distinguished, from its fellows by the fact that here only the purely mechanical process is regarded, while the inner factor, the Will, apparently is not taken into account. This, however, is the real source of intuitive perception, the highest excellence of all poetry.

Says Horace: "Thou seest how Mount Soracte stands forth, white, clothed with a mantle of deep snow—the groaning branches bend beneath its weight —rivers and brooks, rigid with frost, are arrested in their course." All of which is external causality, external change, highly characteristic by reason of its contrast to the previous natural state of things, when Mount Soracte was clothed in green, when the trees

[39]

spread forth their branches, and the brooks sped restlessly along.

The converse of the last condition is illustrated in the following parallel German and Latin statements:"Diffugere nives, redeunt jam gramina campis,

Arboribusque comae.""Vom Eise befreit sind Strom und Bäche

Durch des Fruhlings holden belebenden Blick.""Es lacht der Mai,

Der Wald ist frei

Von Reif und Eisgehänge ;

Der Schnee ist fort,

Am grünen Ort

Erschallen Lustgesange."[Snow disappears, and already the grass in the meadow is sprouting, Foliage covers the trees.]

[Released from ice are brook and river

By the quickening glance of the gracious spring.][May smiles in glee

The woods are free

From ice to branches clinging;

The last snow yields,

In fresh green fields

The birds are gaily singing.]All these, once again, are external changes, conceived as causality—the more effective and the more expressive, the stronger the contrasts that connect them. In this passage, however, as it ever is in poetry, the internal, the animate, is revealed in utterance like "holden, belebenden Blick" "Es lacht der Mai" "Lustgesange" and "Vom Else befreit" Grand and sublime poetical passages frequently owe their beauty to the manifest disproportion between cause and effect, wherein a trifling external cause produces some tremendous effect, which vividly illuminates and sets in

[40]

relief the power and might of the author and originator. To this class belongs pre-eminently that celebrated passage of the Bible: "And God said, Let there be light: and there was light."

The simple word is here the cause. Haydn has musically interpreted the last word of this passage by an endless strain of widely diverging accords, illustrating the immensity of the effect in contrast with the simple motive word of command. Handel has expressed the opposite effect in his wonderful work "Israel in Egypt": "And he commanded the sea. And the sea became dry," by introducing the command as overpowering and omnipotent, whilst representing the effect pianissimo—the sea humbly obeying. Both composers strove to express the same by opposite methods. Haydn depicts the majesty of the Creator by the greatness of the effect; Handel, by the: audible diminution of the effect, which, nevertheless, is conceived as great.

Here belongs also that sublime passage of Homer, in which Zeus, by the mere movement of his dark eyebrows, and by a nod of the head, causes great Olympus to tremble — a passage, the beauties of which three Roman poets have imitated: —Horace: Cuncta supercilio moventis.

Virgil: Annuit et totum nutu tremefecit Olympum.

Ovid: Concussit terque quaterque

Caesarem cum qua terras, mare, sldera movlt.Here, in order that the soul may vividly apprehend the overpowering might of the Thunderer, a mechanical effect is to be assumed throughout, — the effect of external upon external. Of course, I do not deny that in the humbly obeying sea we may also assume an ethical effect, and, at the same time, a mythological

[41]

form of expression. Here is portrayed the living God, who has created all things, whose voice, therefore, is listened to with trembling and awe, and is forthwith obeyed by every created being.* * *

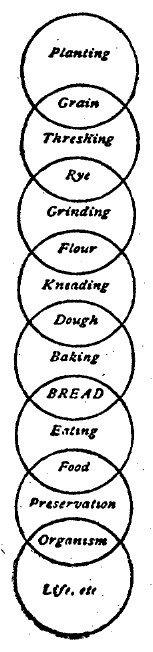

What the Logos is, how many contradictions it must reconcile in order to become what its name purports, may be seen generally from my work. The independence of our percepts, due to their having assumed in the mind definite lines of demarcation, and to their having been placed at the disposal of the intellect, so that they can be summoned forth at any time by the word and the general concept — such is the highest achievement of the Logos. With this performance, the Logos entered into existence. This character of combining and distinguishing, it still preserves in all its functions, as, from the beginning so to the present day, when infinitely complicated mental operations are performed with instinctive certainty and lightning rapidity, so that it seems almost impossible to follow the course of the individual threads. For the sake of greater clearness I shall attempt to show, by means of the accompanying cut, what elements of thought of a simpler order, and likewise concepts, may be contained in a single concept, and how through the reciprocal interaction of these concepts and of the per-

[42]

cepts which they control, a concatenation of ideas converges in that concept, and likewise again radiates from it. The concept Bread is chosen. In our cut the concept is developed genetically toward the top, and ideologically towards the bottom. Proceeding from the top and bottom, respectively, the concept becomes ever more special, that is, it includes more definitions. Starting from the middle, it passes into ever more general concepts, which by reason of their more general character can all be predicated of the notion Bread, or be referred to it.

By an illustration of this kind it can be graphically shown, how ideas can assume for man the part of things real; how man has acquired the power of bringing together in his representative faculty the most remote objects, and how he has thereby been enabled to accomplish the great miracles of human industry and commerce. But all this would be utterly inconceivable without concepts, which impart to percepts their unity and self-dependence, and bring about and multiply their rational connection. Hence, also, no animal can ever advance a single step beyond present perceptive representation, can never escape from the constraint which Nature has put about the narrow sphere of its wants. Unfortunately, however, in apparent contravention of this rule, ants to the present day carry on a regular and methodical species of agriculture, keep live-stock and domestics, like we! Nay, they have even been caught in conversations and social entertainments of a full quarter of an hour's duration — Heaven save the mark!* * *

[43]

The perception of causality subsisting between things! Verily, this constitutes such a simple, plain, and at the same time obvious and convincing means of distinguishing the Logos, human reason, from animal intelligence, that it seems inconceivable that this manifest and clear boundary-line should not long ago have been noted, and established as such. That this causality could be grasped by the mind, one of the two causal members must at the start have necessarily existed as a percept or representation only, and its connection with the others been effected by thinking, that is by means of the concept. In "dug here" the present aspect of the phenomenon refers to a past activity as cause; in "thing for digging" reference is made to a future activity as aim. In both cases two representations or percepts must be simultaneously present — one of which, accordingly, can only be present by representation; but this can be attained only through the concept, the word. Therefore, man only, and the animal never, will be found in the possession of tools.

The acts of a cognising man, through the percepts that illuminate consciousness, seem to be connected with one another, that is, governed by inner necessity.

Yet who could remain blind to the truth, that the percepts connected with the will are the most natural and most primitive of all; that practical thinking, if I may use this expression, or, thinking guided by interest and founded on the subjective basis of will, must alone be placed at the beginning of this development, seeing that even today it forms the life-interest of the majority of men? The emancipation of our

[44]

thought from our desires and wants constitutes every advance towards theoretical knowledge, and it certainly follows thence, that originally thought was wholly coalesced with will; that percepts, accordingly, in the consciousness of primitive men, were not arranged in any causal, genetic, or intellectual connection, but simply in the order in which through instinctive impulses and emotion they had entered their various incidental or natural connections. The will for a long time remained absolute autocrat; all speech aimed at practical effects, sympathetical agreement, and incita-tion to common action. From the earliest, instinctive utterances of will, which, in the shape of sounds simultaneously uttered, encouraged men to perform the primitive acts of digging, plaiting, etc., up to the kindling eloquence of the popular orator who fired the souls of his audience with martial enthusiasm, by his vivid picture of desecrated graves and temples, of cities laid waste, of women and children dragged away into captivity — throughout the same law unceasingly operates, the action of will upon will through the sympathetic frame of mind and its attendant percepts. Everywhere we find imitation, everywhere will, everywhere activity. And for this reason my theory, which erects upon this basis all that exists, has justly received the name of the Sympathy Theory.

We see the active causality of our will produce effects, and, as it were in a dream, create forms, which upon being taken up by the senses (passive causality), are converted into percepts, to enter again our consciousness as the reflected activity of volition. This, however, is not a succession, although it may appear

[45]

to us as such, but actual simultaneousness, unity, the essence of causality and reason. One of the most important aspects of my theory is therefore aptly expressed by the designation Causality Theory.

But the most important element is still lacking — the free, regular, and well-arranged combination of the percepts, as guided and irradiated by the light of cognition, in a word, the Logos. For, despite the unity of causality in the cases hitherto considered, the percept still strongly clings to the will, to sensation, and direct sensory intuition. To release it (the percept) from this bondage of coarse, empirical reality, to elevate it irrevocably into the ideal sphere in which with perfect mental freedom it can enter innumerable other combinations — to achieve this miracle, causality must emancipate itself, and become a powerful and ever ready instrument of the human mind.

Causality gained freedom solely through the rise of concepts and words. The oldest words, dig, plait, bind, separate, have no other content than that of causal relation — the connection of two sensually perceptible percepts that constitute their causal members, the Logos.

The causal relation implied in all concepts and words, that is their verbal fluidity, which has its true basis in its derivation from activity, taken together with the substantiality of the percepts themselves, renders possible their union and junction with one another. In this manner words and concepts are brought together and unified in the human judgment, and with this we have reached abstract thought, and its ultimate principle, the "ground of cognition," represent-

[46]

ing the second class in the Schopenhauerian distribution. But all judgments, of whatever kind they may be, have as their final condition merely intuitive percepts, from which they proceed, to which they rede-scend from their abstract altitude, and with reference to which, perforce, they must find their application. The union of percepts with percepts, of concepts with concepts, of judgments with judgments constitutes, accordingly, the essential character of thought. But all this is Logos, and, consequently, my theory of language is most fittingly and properly designated the Logos Theory.

[1] That part of the chapter of the original which explains the other three categories is omitted. The other three are: the effect of external on internal; of internal on external; and of internal on internal.

- Centre de recherches en histoire et épistémologie comparée de la linguistique d'Europe centrale et orientale (CRECLECO) / Université de Lausanne // Научно-исследовательский центр по истории и сравнительной эпистемологии языкознания центральной и восточной Европы